Critical polyamorist blog

|

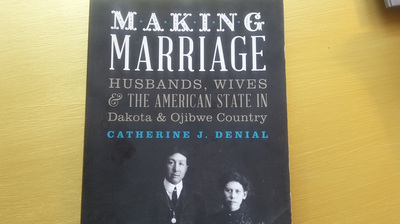

If I were a country music singer I’d write a song by the same title as this blog post. I would love to be an ethical nonmonogamist, sequin-sporting, cowboy boot wearing Native American country music star, belting out radically different narratives of love, lust, and loss. Steel guitar and fiddles would scream behind me. But I digress.

I left a state sanctioned legal marriage in 2010, or so I thought. We have never legally divorced. I don’t care about the legalities. We are still financially and socially entangled as coparents, and we occasionally collaborate professionally. I don’t plan on marrying again. I will always be responsible financially to my coparent’s wellbeing, if he needs me to be. He has been my closest friend. There are also benefits to being legally married in the US, that settler state of which I am a citizen and where my coparent still resides with our child. The US denies its citizens universal healthcare and makes it difficult for “alternative” families (i.e. not heterosexual and/or monogamous) to enjoy rights of visitation in hospitals, or easier child custody arrangements. Legal marriage, including same-sex marriage, helps deliver these benefits. Marriage can also provide tax benefits, cheaper insurance and other financial incentives. Living in two separate households is expensive enough. The financial perks of remaining legally married help even though I now feel deeply negative about the institution. Such benefits should not be reserved for those who are coupled in normative, monogamous unions constituted along with legal marriage. But this powerful nationalist institution reserves for itself the utmost legitimacy as an ideal social form, one we are all supposed to aspire to or we are marked as deviant. It asserts its centrality at the heart of a good family. It forecloses other arrangements and choices. Even after I tried to abandon settler marriage, it continues to break my heart year after year as I struggle to live differently in a world so fundamentally conditioned by it. I wrote in a July 2014 blog post, Couple-centricity, Polyamory and Colonialism, about this form of relating and how it was imposed to build the white nation and decimate indigenous kin systems. The diverse ways of relating of other marginalized peoples, e.g. formerly enslaved African-Americans post-emancipation and their descendants, LGBTQ folks, and those from particular religions that advocate plural marriage (my readers may have less sympathy for the latter) have also been undercut by settler norms of sexuality and family.[1] The High Cost of Resisting Compulsory Monogamy In 2010, I was still brainwashed by compulsory monogamy. I was deeply pained by not feeling what I thought I was supposed to feel in a lifelong, coupled relationship. I thought if I found the “right” monogamous relationship my confusion and pain would be no more. But I did not entertain that idea for long in the separation. I cannot honestly remember why I decided to explore ethical nonmonogamy, at first by reading, and then by actively engaging with an ethical nonmonogamy community in the city I moved to. In the several years since I began living as a nonmonogamist, I have climbed a steady learning curve. Many of those lessons are documented in this blog. But despite my realization that settler sexuality and family are the source of much anguish for me, for my extended family in our mostly “failures” to attain it, and for indigenous peoples more broadly, I have consistently known that if I could go back in time to 1997, I would get married all over again. We brought our daughter into this world. I would change nothing if it meant she would not be here. Being the cultural person I am, I live according to the idea that there is a purpose that I will probably never fully name to our daughter’s presence in this world. I cannot imagine this world without her. I would do every single thing exactly the same in order to make sure that she arrived in this world exactly the person she is, both biologically and socially. I understand those aspects as co-constitutive. That is, we are biosocial beings. But even aside from our daughter, I would get married all over again. Had we not legally married he would have moved overseas without me for a once-in-a-lifetime job opportunity, and that would have ended our relationship. We had to be legally married, according to immigration, for me to accompany him long-term. I would marry him all over again because I grew enormously with him. I don’t know if he would say the same. I hope so. If he would not, that would be sad. We spent so many years together. My daughter’s father is someone with whom I have always questioned my cultural and emotional fit. He is not a tribal person. Those are the people I connect emotionally most deeply with. Yet he and I have a deep and abiding intellectual and political fit, and I have not been able to let that go. We never ever lack for ideas to discuss together, and with such animation. We think and write well together. We are highly intellectually complementary, and that matters to us since we both do intellectual work. Physically we are a good match as well, except for me sometimes when the cultural connection felt not enough, when I especially longed for that kind of emotional intimacy, and which no doubt I did not provide for him either. There are things I will never understand about him. I attribute that to our very different cultural upbringings. I would grow detached, retreat physically. I eventually accepted that he was not the right one. Yet I see why I got together with him, and why I kept coming back after several attempts early on to leave, why I ended up staying so long. And yet I also cannot regret leaving. I simply don’t see how I could have done anything differently given who I was, and who he was each step of the way. I did not take the easy way out. I tried hard for years to understand. It was only through staying, and then finally leaving, and then studying and practicing ethical nonmonogamy that I came to understand the structures that produced our relationship, and which continue to. I know that there was no other choice but to eventually leave. I have revisited this decision many times. Each recollection, I arrive at the same conclusion. The unhappiness was growing too large. My behavior in the marriage too deteriorated. I grew to dislike my coparent and myself more every day. I had liked us both when we got together. I finally couldn’t live like that. I had respected us both. I wanted to respect us both again. I had so much to change. I see many couples out in the world mistreating one another, or suffering in silence. Between my own marriage and the nonmonogamous relationships I’ve been in, both with divorced people and with those attempting to make their marriages work, I know how pervasive are unmet needs, the resentments and sadness that come for so many with compulsory monogamy. I see these dynamics everywhere now. And I no longer see them as individual failings. For many people, there are few real choices. Our society does not want to accommodate anything but compulsory monogamy. It insists on the right one, until death do you part, settling down as a mark of maturity, making a commitment with a narrow definition of what that looks like. Society then stigmatizes multiple needs and vibrant desire as commitment phobia, wanderlust, sordid affairs, promiscuity, cheating. Indeed, our society better accommodates lying than it facilitates openness and honesty. While I am able to choose not to lie, to be openly nonmonogamous with my partners, it has come at a significant emotional and financial cost to all involved when I left a normative marriage to eventually figure it out. Only if I were who I am now could I have made a gentler, wiser choice six years ago. Only if I were an ethical nonmonogamist then could I have tried to make another decision, and asked my coparent to join me in that. He is an anti-racist, anti-colonial, sex-positive feminist. Chances are he would have tried. But I was not who I am now. It was an intensive, committed journey to get here. I also know long-together couples in open relationships who work well, who love and respect each other and their other partners, and whose children are well taken care of. Ethical nonmonogamy, if it were a legitimate social choice that we were taught early on, like we are taught compulsory monogamy from our first consciousness, would enable more expansive notions of family thus keeping families more intact. I probably would not have left. I would have known then that no one partner, even a culturally more familiar one, could provide all I need. A different kind of marriage is a marriage I can probably get behind. This is one reason, despite my misgivings about the Marriage Equality movement, I do think queers getting married will trouble our mononormative conceptions of marriage as part of their critiques of heteronormative marriage. Queers more often do ethical nonmonogamy. If anyone is going to marry, better queers than straights in my opinion. Crying the Nights into a Coherent Narrative Six years into this transition, I have begun crying myself to sleep each night, either at the beginning of the night, or sometimes in the middle. I never sleep the night through. My tears do not represent regret. They mourn ongoing, inevitable loss. Crying is like composing, whether words, or song, I imagine. I let the nightly cries take me as if they are a spirit possession so strong it is easier to submit. I work through them as hard forgings of language that are at first raw, then sensical, poetic. It is a form of intellectual intercourse with the emotions of my body, with history, with the planet and skies. My days are bright and pass quickly with vibrant intellectualism—with measured hope in an era where many have little. Why then are the nights so hard? After much pondering, I think I know. The nights this far north are expansive in their starry blue-blackness. And though they grow shorter, squeezed on both ends by sun, they are somehow not smaller. The night relinquishes no power. History and auto-ethnographic data flood in to widen the hours of unsleeping. Until finally I fall asleep without realizing. I am not a person who can live content without understanding. I was deeply troubled in a normative marriage. In order to change anything, I had to understand why. It took me six years of active study of myself, of texts, of others to understand. During the last few months, in the long nights of reflection and in deeply physical bodily mourning, I have come to know that I could have done nothing differently. Under the weight of settler history, I had a narrow range of choices. Of course I do not feel blameless. My love and longing for my daughter won’t allow that. My nightly cries have now become simple mourning of every night lost with her—every night that I cannot hug her goodnight, or rub her back until she falls asleep. She is a teenager now but like all of the children in our extended family, she likes to sleep with her mom. I mourn the loss of cooking dinner with her in the evenings, her chatter in the kitchen, her eagerness to learn how to cook. I mourn her beautiful singing voice daily, seeing the progress of her paintings weekly in the art studio. I miss giggling and plotting and whispering with her in person. I left a marriage that her father had a much easier time fitting into. Settler marriage was a model that more or less worked in his life experience. He was always her primary caretaker. I could never have asked to take her with me, not then anyway. I also left for a nonhuman love it turns out, although that took me a while to realize. I needed to be back on the vast North American prairies. My coparent loves living near the sea. While I am fed by multiple partial human loves I cannot do without that land-love. So I am thankful for Skype. I am thankful for jet planes. I am thankful that I mostly have the means to make this work. But the distance cuts hard, especially in the middle of the universe of night when I am far from my daughter, when I hear matter-of fact thoughts in the crystal quiet: Things might not end well. There are no guarantees. Yet maybe “ending well” is a vestige of monogamy, a vestige of the utopic but destructive ideal of settlement in its multiple meanings: not moving or transitioning; settling for the best thing we can imagine; closure, no open doors. But a life in which our child lives long plane rides away from one or the other parent seems a sad alternative to the settler monogamy and marriage I cannot abide. So much travel feels ultimately unsustainable—emotionally, financially, and environmentally. I think of refugees of war, or economic migrants who live through different sets of oppressive circumstances half a world away from their loves, both human and land. I try not to feel sorry for myself. I still have so much. I try to have faith that I can keep patching together my loving relations over an arc of the globe for as long as I need to. I try to have faith in new ways of knowing and being, ways that scare me. I am in uncharted territory. I hope I can keep going. Maybe something will change. Ethical Nonmonogamy as a Site of Biocultural Hope Settler marriage, sexuality, and family have been cruel and deep impositions in my people’s history, and in mine. My ancestors lived so differently. I think we tribal peoples are left with pieces of foundations they built. What we have been forced, shamed, and prodded into building in their place is an ill fit. But it is not like we have plans or materials to build as our ancestors did. We go on as best we can with what we have. My ancestors had plural marriage, at least for men. And from what I read in the archives “divorce” was flexible, including for women. Women controlled household property. Children were raised by aunts, uncles, and grandparents as much or more than by parents. The words in my ancestors’ language for these English kinship terms, and thus their roles and responsibilities, were cut differently. I know one feminist from a tribe whose people are cultural kin to mine who speculates that maybe the multiple wives of one husband may sometimes have had what we call in English “sex” with one another. (I assume when they were not sisters, which they sometimes were.) And why not? In a world before settler colonialism—outside of the particular biosocial assemblages that now structure settler notions of “gender,” “sex,” and “sexuality,” persons and the intimacies between them were no doubt worked quite differently. Much of the knowledge of precisely how different they were has been lost. Oppression against what whites call sexuality has been pervasive and vicious. Our ancestors lied, omitted, were beaten, locked up, raped, grew ashamed, suicidal, forgot. We have inherited all of that. I live and work in pursuit of new ways of loving, lusting, and losing amidst the ruins and survivals together of my ancestors’ ways of relating. I work with what is left to work with. I take note of the historical accounts we retain, both in academic English and in our oral histories. I look to articulate these partial understandings with my lived experience in tribal community and the fundamental ethical lessons I’ve inherited from my people. Even in the instances where specific knowledge of cultural practices was beaten and shamed out of our peoples, I believe that we have retained in community fundamental ethical orientations to the world that can help us learn to love and relate in the 21st century in ways that are less conditioned by the specific settler structures of sex and family against which I live and write. Some of these ethical orientations include a sense of agnosticism about what we know and withholding judgment, a humility and patience to wait for more information; a sense of relatedness to other living beings rather than fundamental rights to own or control; a broader and less hierarchical definition of life (born of that agnosticism) than Western thinkers have tended to allow; a sense of being in good relation that is measured by actual relating rather than by doctrine; and finally not simply tolerance for difference but genuine curiosity about difference, and sometimes even delight in it. In my loving and relating, I look for and seek to proliferate “sites of biocultural hope” as my colleague and friend Eben S. Kirksey describes them. In what has been dubbed an anthropogenic age, in which humans have developed the capacity to fundamentally alter the Earth’s climate and ecosystems, Kirksey advocates something more than apocalyptic thinking. He is one of the non-indigenous thinkers with whom I am most in conversation. He encourages us to understand surprising, new biosocial formations in an era of environmental, economic, and cultural crisis as legitimate flourishings, and not simply deviance. Where Kirksey refers to "emergent ecological assemblages—involving frogs, fungal pathogens, ants, monkeys, people, and plants," I do not forget such other-than-human relations. But I also refer to indigenous peoples and cultures in the wake of American genocide as not only sites of devastation, but as sites of hope. My particular people have been post-apocalyptic for over 150 years. For other indigenous peoples it has been longer. Still, our bodies and continuing/emergent practices are ecosocial sites and manifestations of hope. We survive, even sometimes flourish, after social and environmental devastations, after and in the midst of settler cruelties from extermination to assimilation designed to wipe us from this land. I see us combining our fundamental cultural orientations to the world with new possibilities for living and relating. We’ve been doing this collectively in the Americas for over five centuries. We’ve done it with respect to syncretic forms of religion and ceremony, with dress, music, language, art and performance. Why should we not also articulate other ways to love, lust, and let love go? Settler love, marriage, and family in hetero- homo- and mononormative forms does not have to be all there is. I have to have faith in that. I am only beginning to imagine. Yours, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Katherine Franke. Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Equality (New York: NYU Press, 2015). Also see Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and Nation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) and Sarah Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press 2008).

8 Comments

Janice Williamson

5/29/2016 08:01:07 pm

I always ask myself "what is at stake" in writing and here everything is at stake. This brilliant insight and suffering of making a life makes me weep. How it is we live in relation? The death do us part rapport with our beloved children. The essential sanctity of our libidinal erotic bodies. Our lineage in the human or nonhuman species echo chamber. Our knowledge of the fundamental limits of compulsory heterosexuality. Our recognition of the legacy of misogyny and racism. And our skeptical interruption of the confined neoliberal consumption unit called the settler nuclear family. You invite us into a meditation on what it means to honour an enduring kinship network filled with possibilities for all our sexed gendered bodies. We imagine ourselves thriving within and without this network of connections. This text maps - eloquently - vexation and loss and that transformative energy called reflection/action/hope. Grateful for this provocation to remake our lives. Love love xoxox

Reply

Critical Poly

5/29/2016 09:17:42 pm

dear janice, thank you for that beautiful comment. i write to think things through in conversation with others who have traveled this journey in some way. i write in order to find you all.

Reply

6/1/2016 06:34:51 pm

Wow, yes. Damn, I feel this so much- and feel strange that I do so, since I am technically a 'settler' to north america myself... but one who eschews the monogamy-capitalism paradigm.

Reply

Critical Poly

6/2/2016 01:35:16 pm

...and i feel the same with your words, mel mariposa. keep doing and broadcasting your good work. folks who want to pursue ethical nonmonogamy need all the resources and encouragement they can get.

Reply

Ray

7/23/2016 11:45:03 am

Although I've felt it all along, I've never been able to quite pin down this kind of "not belongingness" and some kind of melancholic loss that lurks here and there on the margins of life. Your story evokes it in a different (but somewhat similar) sense for me in that I was born deaf but raised in the hearing world so I don't quite exactly fit in either, sort of caught in between worlds. I'm also a bit of an extreme introvert (and a wandering one at that, currently meandering across Canada as a solo traveler in a tiny camper), so that also defies social norms. Is it really such an alien thing to follow our calling and do/enjoy what we love -- whatever is it we do and however we desire relate to/with others?

Reply

Critical Poly

8/4/2016 09:24:09 am

dear ray,

Reply

Crow

11/23/2016 01:01:08 am

This has been.... beyond profound. I am a poly bisexual woman and my fiance is Lakota and also poly. He has walked the Red Road... since the day he was born. I've been walking the Red Road with him for 3 years now. I've been waiting patiently... trying to hear from others who understand the deep, unsettling sadness that comes from being in a monogamous relationship. You have put it all.... so elegantly. Words fall short... it takes my breath away, so my head swims with delight as I read. I thought I was... alone in wishing for a simpler, tribal time; as I do not fit into the white cis world at all. One where you can simply exist as you were meant to be, where your heart can truely lead your life, without the disconnect that sometimes happens in monogamous, settler paradigm.

Reply

Critical Poly

12/22/2016 05:37:59 am

thanks crow, for your comment and for following my blog. you remind me that i need to get back to it. it's been a time of transition this year and there is much to write about.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Photo credit: Short Skirts and Cowgirl Boots by David Hensley

The Critical Polyamorist, AKA Kim TallBear, blogs & tweets about indigenous, racial, and cultural politics related to open non-monogamy. She is a prairie loving, big sky woman. She lives south of the Arctic Circle, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can follow her on Twitter @CriticalPoly & @KimTallBear

Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|