Critical polyamorist blog

Keynote lecture given at the Second Annual International Solo Polyamory Conference (SoloPolyCon18), Seattle, WA, USA, April 14, 2018 During the weekend of April 7-8, 2018, I attended Converge Con in Vancouver. It is a conference “that originated with a desire to build sex positive communities, and start a dialogue around sexuality, relationships and activism.”[1] I had the honor of being on the closing panel, #MeToo in the Age of Consent, with Erin Tillman, the author of The Consent Guidebook, and sex educator, Jimanekia Eborn—both from L.A. The final question posed to our panel was: If there was one thing you wanted people to take away this weekend about autonomy, agency, power, and creating a culture of consent, what would that be? “Remember your structural analysis,” I responded. Settler sexuality—that gives us this hetero- and increasingly homonormative compulsory monogamy society and relationship escalator intimately tied to settler-colonial ownership of property and Indigenous dispossession--is a structure. Converge Con was refreshing with so many people with similar filters about sex-talk, meaning…let’s talk unabashedly about sex. All of it! They set up a separate social space for between session gabbing because in 2017 there were complaints from “normies” at the hotel about all the sex talk happening in the lobby. At Converge Con sessions included “Group Sex Demystified,” body positivity, liberation from repressed sexual shame, sex positive parenting (loved that one), “Masturbation for Healing and Creation,” “How Society’s Representation of Beauty…Impacts Sexual Self Expression,” and how to manage sex and relationships when coping with depression. There were many sessions that teach us as individuals, couples, families or even communities techniques for liberating ourselves psychologically, emotionally, even spiritually from sex negative and shaming thoughts and behaviors. I found less emphasis on averting our gazes from our own bodies, individual, family, or community histories to look hard at the (settler) state and its structures. Those structures not only indoctrinate us with settler ideals, but they have legally and economically enforced certain forms of sex and relationships throughout the existence of these nation states. It is necessary to throw off shame, love one’s self and one’s body, rejuvenate, and practice self-care. Yet a focus on even sex positive bodies and relationships vs. a focus on sex negative bodies and relationships, is not in and of itself a structural analysis. Focusing on sex and body positivity helps us cultivate the energy to fight systemically. And personal transformation cannot fully occur without societal transformation. The two are co-constitutive—meaning individual and societal change help produce one another. I want us to always keep that in mind. The heteropatriarchal state would prefer we focus our eagle eye on our own shortcomings exclusively, and not its extractive and oppressive structures. A Note on Terminology: Settler and Settler Sexuality My colleague at Queens University, queer theorist Scott Morgensen, has popularized in academic circles—and this bleeds into Indigenous sexual health circles—the term “settler sexuality.” He defines this succinctly as: The heteropatriarchal and sexual modernity exemplary of white settler civilization.[2] If that is too succinct, he has also explained settler sexuality as: A white national heteronormativity [and increasingly also homonormativity] that regulates Indigenous sexuality and gender by supplanting them with the sexual modernity of settler subjects.[3] His work and the work of other anthropologists and historians of Euro-American settlement, marriage and monogamy in the US and Canada, shows how it was not only Indigenous people that were forced into monogamy and state sanctioned marriage.[4] Those relationship forms were intimately tied up with the appropriation of Indigenous collectively held land and its division into individual allotments to be held privately. Men as heads of households qualified for a certain acreage. They obtained more if they had a wife and children. Women of course were tied to men economically. Accordingly, compulsory monogamy and marriage have been forced on other non-monogamous and sometimes non-Christian communities as well. Thus, settler sexuality can be translated more straightforwardly as both heteronormative and homonormative forms of “love,” “sex,” and marriage that are produced along with private property holding in the US and Canada. Therefore, when I use the term “settler,” I am not interested in nitpicking who is and is not a “settler” on an individual level. Americans often find the term odd, too polite, actually. On the other hand, more Canadians are a bit more accustomed to “settler,” and don’t often find it so polite. Some of them seem to have the same reaction to the term “settler” as they do to being called “white.” But I also know many academics, both white and “visible minorities” (the term used frequently in Canada for “minorities” or “people of color,” and which includes recent immigrants) who identify as “settlers.” And when they do, it is with explicit recognition that their lives in Canada are made possible by settler-colonialism. There are vibrant conversations in Canada and in the US (although more so among academics in the US) that debate the applicability of the term “settler” and suggest new terms for non-racially privileged, non-Indigenous groups, e.g. African-Americans or recent non-white or non-Christian immigrants who enter the US or Canada due to conditions of war and violence in many cases due to settler state imperialism abroad. There will be no untroubled definitions of the category of settler. Instead, I focus on settler-colonial state power, including its cultural power, which all of its citizens are capable of shoring up. I see non-Indigenous racially disadvantaged citizens as potentially complicit in settler-colonial appropriations of Indigenous (re)sources. And many of us across racial and religious lines have been made complicit in helping uphold settler forms of sex. Kyle Powys Whyte, a Potawatomi environmental philosopher and activist who teaches at Michigan State explains very pithily how the citizenry broadly is involved in ongoing settler-colonialism. In a recent article in Yes! Magazine, he writes: Whether one participates in settler colonialism is not entirely a matter of when or how one’s ancestors came to the U.S. Having settler privilege means that some combination of one’s economic security, U.S. citizenship, sense of relationship to the land, mental and physical health, cultural integrity, family values, career aspirations, and spiritual lives are not possible—literally!--without the territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples.[5] Are Non-normative Sexualities also “Settler Sexuality”? So-called non-normative sexualities and relationship practices, such as polyamory—I would say especially solo polyamory within that--do challenge important settler state cultural restrictions, but they also tend to assume the inevitability of settler-colonial cultural norms and governance structures. They do not sufficiently interrogate Indigenous dispossession for the rise of a private property state. They often simply want to redeem the settler state into a more multicultural and inclusive entity, without asking how even alternative practices of intimate relation uphold settler colonialism. Margot Weiss, an anthropologist who wrote a book Techniques of Pleasure that examines kink communities in San Francisco and Silicon Valley shows how they consume expensive sex toys and “play” experiences on their way to personal self-actualization. She highlights gender and race dynamics and power relations in kink communities that are sometimes not so different from mainstream settler sexuality. These patterns of individual identity-making via capitalist consumption, and fairly normative race and gender dynamics rose in concert with settler-colonial nation-building. She also delves a bit into the very interesting history of old guard leather communities in San Francisco that have had more oppositional politics historically, but her focus is on newer more economically privileged kink communities, including tech sector workers. Scott Morgensen in his anthropological work in a community of radical faeries and their predominantly white back-to-the-land communities also shows how even queer sex, including non-monogamy and kink are also often enacted as forms of settler sexuality. Morgensen’s work shows how radical faeries in a rural Oregon community remain conditioned by race hierarchy, and their back-to-the-land ideology is of course predicted on Indigenous dispossession historically and erasure of Indigenous presence today. Morgensen discusses how queer claims too are conditioned by settler colonialism. He also pays close attention to Indigenous two-spirit activism and theorizing and their focus on People or tribal-specific knowledges about sexualities, relations, and relationships. The term “two-Spirit" gestures toward precolonial gender systems not based on the European sex/gender binary that concerned colonizers and which now concerns queer thinkers. If you don’t know the history of the term two-spirit, which is in wide use today, it came into common use in 1990 in Winnipeg at the International Gathering of American Indian and First Nations Gays and Lesbians.[6] As opposed to “coming out,” an important aspect of two-spirit thought is the idea of “coming in” to community to take up special roles designated for gender diverse individuals within the extended kinship webs of Indigenous communities historically. Or at least that is the ideal. Two-spirit people have struggled in Indigenous communities too with homophobia produced of colonial violence. In my Critical Polyamorist blog, I’ve written about the disproportionate influence that heteronormative couple privilege and associated hierarchies have in polynormative communities. My frustration with that mode of polyamory is explained in my critiques of how it remains very much a form of settler sexuality. More rule-bound and couple-centric forms of polyamory privilege the married, cohabiting, child-sharing couple as “primary,” with additional relationships being “secondary.” This replicates key conditions of monogamy that I find politically and ethically difficult. In short, it is not only vanilla monogamists who uphold settler-colonialism with their intimate practices linked to property, consumption, couple and marriage privilege. Within open nonmonogamy, I push for analyses that help us envision ways of relating beyond such normative arrangements and also beyond Western notions of romantic “love” conditioned—whether we know it or not—by capitalism’s coercive power. I don’t want Hallmark and Nestlé telling me when and how I need to show my love while also giving those companies my money to evangelize normative relations and unsustainably extract resources. SoloPolyamory and Being in “Good Relation” I am here with all of you at SoloPolyCon because I see more potential in solo polyamory for challenging the assumptions of settler states. I’ve considered too the potential for my focus on being in good relation—my particular Indigenous standpoint—to be in conflict with the ethic of autonomy and non-hierarchy that is a mark of solo polyamory. But then I remembered a photo that one of you posted on Facebook during last year’s conference. (I was sick and had to Skype in my talk from Edmonton.) The photo was of about a half dozen SoloPolyCon attendees hanging out at the beach. They were each standing apart, scattered along the beach like differently contoured and colored stones. And I remember the photo was captioned “Alone together.” The image looked so appealing, just the kind of community that would understand me and that might be able to be articulated with the idea of being in good relation that is being taken up with renewed commitment by different Indigenous peoples across North America these days—by academics, artists, activists, and Indigenous Twitterati. I cannot emphasize how much Indigenous thinkers are focusing on “Indigenous relationality,” an umbrella term used to help us think beyond race, the nation state, biology, and other settler conceptual impositions. Taking the “solo polyamory” explanation from our Facebook page: People who practice solo polyamory have lots of kinds of honest, mutually consensual nonexclusive relationships (from casual and brief to long-lasting and deeply committed). But generally, what makes us solo is the way we value and prioritize our autonomy. We do not have (and many of us don't want or aren't actively seeking) a conventional primary/nesting-style relationship: sharing a household & finances, identifying strongly as a couple/triad, etc.[7] How do I see that as being articulated with the idea of Indigenous relationality? Autonomy from compulsory monogamy or even the nonmonogamous hierarchical couple need not be defined as “single.” Solo polyamory for me is a de-escalation from the couple. For me and others it is a refusal to get on the escalator (again). But it can simultaneously also lend itself to living in extended relation and disrupting commonly accepted relationship categories. Many of us work to build networks of made kin as essential support systems, and with more fluid boundaries. And many of us do this under settler structural duress. It’s just that most solopoly people probably don’t name the challenges they face as settler-colonialism. I’ve written and talked elsewhere about my Dakota ancestors’ practices of relating and their “sexualities” as we call it today. Before settler-imposed monogamy, marriage helped to forge important Dakota kinship alliances, but divorce for both men and women was possible. Women also owned household property. They were not tied to men economically in the harsh way of settler marriage. More than two genders were recognized, and there was an element of flexibility in gender identification. People we might call “genderqueer” today also entered into “traditional” Dakota marriages with partners who might be what we today consider “cisgendered.” In a world before settler colonialism—outside of the particular biosocial assemblages that now structure settler notions of “gender,” “sex,” and “sexuality,” persons and the intimacies between them were no doubt worked quite differently. In thinking about “sex,” how did my ancestors share touch as a form of care, relating, and connection before the imposition of settler structures of sexuality and family? There is much that has been lost due to forced conversions to Christianity and the sexual shaming that came with that. And so much of settler sexuality has been imposed onto Indigenous peoples in place of our ancestors’ practices, both heteronormative and now also “queer” settler sexuality. But in a world before settler colonialism and its notions of “gender,” “sex,” and “sexuality,” persons and the intimacies between them were no doubt worked quite differently. And yet, we Dakota continue to live in a way that embodies in our 21st-century loves, long-held kinship structures. Many of us continue to live in extended family where the legally married couple is not central, where children are raised in community, and where households often spill over beyond nuclear family and across generations. Can we not then also imagine sexual intimacies outside of settler family structures? I know we already have them. Can we name and measure them without using settler sex and family forms as reference points? It is also important in unsettling settler sex and family to mine historical and language archives in order to know more about what kinds of relations were possible before settler-colonial impositions, including nonmonogamous relationships that were common in Dakota and other Indigenous cultures. This suggestion will be met with resistance by some Indigenous people. Our sexual shaming and victimization has been extreme at the hands of missionaries, in residential schools, and by government agents who all wielded violent control over Indigenous lives. There are still many of us have not recovered from the shaming of Christian sexual mores, and supposedly secular state institutions that continue to monitor, measure, and pathologize our bodies and our peoples. That said, I am beginning to hear from younger Indigenous people either via comments on my blog or when I give lectures at universities, that they would like to embrace open and honest nonmonogamy. But in addition to a shortage of willing Indigenous partners, they worry about the judgement of their elders who are still immersed in values that younger people see as a holdover of residential schools and the church. One Indigenous undergraduate asked me what my elders think of my nonmonogamy. I remember exactly how I responded: I don’t know what they think. They don’t say anything to me, and I’m pretty open on Facebook, and on my Critical Polyamorist blog. But I’m almost 50, and at 55 I'll get a senior discount at businesses on my reservation. I’m almost an elder myself! I also earn my own money and I’m an academic. With that comes more freedom than most people have. So I’m not really worried about what people think. But I know you do have to worry. I try to make space for others so someday they will have the choices that I have. Writing and speaking this talk is to make just a little more space. Yet in our lives as Indigenous people, we already unsettle settler relations in courageous ways. Think about work that Indigenous people do to defend the earth in order to have a chance at (re)constituting good relations with our other-than-human relatives. I think of the resistance to resource extraction that particularly Indigenous women and two-spirit people have organized via IdleNoMore and Standing Rock, sometimes at great personal risk. These are both movements that link the defense of Indigenous treaty rights to defense of the planet, which is a way of also caring for our human descendants to come. In terms of that idea of being in good relation, I consistently compare “environmental” caretaking to caretaking human relations. Accordingly, decolonizing sex is one way of re-constituting good relations with some of our human relatives. Of course I use “relative” broadly since “we are all related.” I will be paying close attention the rest of the weekend at this conference to notice potential articulations between solo polyamory and forms of Indigenous thought and practice related to sex and relationships. Disaggregating “Sex,” Reaggregating Relations: The Example of Moreakamem I want to dig just a bit deeper into the theory behind being in good relation by providing one more example of nonmonogamy and by settler standards non-normative sexuality among an Indigenous people in what is today Sonora, Mexico. There is a type of Indigenous healer there who can teach us a lot about being in good relation in ways that refuse settler sexuality. My friend, David Shorter, an Indigenous Studies scholar at UCLA, wrote an essay entitled simply, “Sexuality.”[8] That essay resulted from the time that Shorter spent with moreakamem—healers or seers among the Yoeme. Being also a religious studies scholar, he had originally set out to understand the “spiritual” aspects of moreakamem as healers. But his analysis came to entangle “sexuality” with “spirituality.” In southern Yoeme in Sonora, an elder told Shorter that individuals who engage in nonmonogamous and/or non-heterosexual relationships are often also moreakamem. In fact, in northern Yoeme communities in Arizona, moreakame has come to be conflated with terms such as “gay,” “lesbian,” or “two-spirit,” and other less positive terms. Indeed, the healer aspect of the word has been lost for US-based Yoeme who have much ethnic overlap with “Catholic Mexican American” communities. But among southern Yoeme, Shorter found that he could not understand the powerful “spiritual” roles in community of moreakamem without also understanding their so-called sexuality. He explains that in many Indigenous contexts, there is an “interconnectedness in all aspects of life.” Following the connections between sex and spirit among the Yoeme was akin to “following a strand of a spider’s web.” Shorter sees both sexuality and spirituality as sets of relations through which power is acquired and exchanged between persons or entities. So when he writes about moreakamem, he emphasizes their focus on relating and their relational sharing of power with those who seek healing, with deities and spirits, etc. The moreakamem have reciprocity with and receive power in their encounters with spirits, ancestors, dreams, animals. And also in the human realm when they use their power to see for and heal other humans suffering from love or money problems, addictions, and other afflictions of mind and body. But moreakamem refuse to accentuate their personal characteristics and capacities. They do not focus on their own so-called sexuality or even their power to heal. Rather, they focus on their work in community. Shorter explains that these healers “work tirelessly and selflessly to maintain right relations.”[9] And he too refuses to classify Moreakamem as gay or nonmonogamous. Shorter also encourages his readers to de-objectify (I might say decolonize). That is, we should try not to think of sexuality, spirituality (and nature too) as things at all. This is difficult: In a settler framework—whether in bed or in ceremony—relations get appropriated if you will and made into “things.” They get named or objectified as “sex” or “spirituality.” David Shorter asks us to see that what settler culture turns into objects are actually sets of relations in which power (and sustenance?) circulates. I am thinking that I would add that our relations then become resources for the settler state to measure, monitor, and exploit to in complex ways build settler knowledge and national identity. This is why I can say we might decolonize relations as we de-objectify them. An important practical outcome of this shift in thinking is that if we resist hardening relations between persons (be they human, nonhuman, or spirit) into objects, we might be better attuned to relating justly in practice, and we might reclaim our relational “resources.”[10] We might attend to being in good relation and what that requires and resist having our relating both stifled and remade by less flexible “natures” and hierarchies. Therefore, It is not only for moreakamem, but for all of us that “sexuality” can be understood as a form of reciprocity and power exchange”—a way of being that “mediates social relations across the family, clan, pueblo, tribe,” etc. We exist not simply in nature but we exist in relation to one another. With this understanding of sexuality, it begins to look as Shorter writes, “more like a type of power, particularly one capable of healing” and transforming.”[11] Think of that co-constitution and re-constitution of our sexualities if we are polyamorous—the multiple, diverse sets of relations, power exchange, and subjectivities that result from multiple relating. I leave you with a powerful quote by David Shorter: Sexuality is not “like” power…sexuality is a form of power: and, of the forms of power, sexuality in particular might prove uniquely efficacious in both individual and collective healing. Further, I will suggest that sexuality’s power might be forceful enough to soothe the pains of colonization and the scars of internal colonization. David Delgado Shorter (2015): 487. Radical Hope Dominican-American writer Junot Díaz expresses two powerful ideas that have been helpful to me of late. In a September 14, 2017 interview with Krista Tippett of the On Being podcast, Díaz explained that in this moment of crisis—and always—it is imperative that critical thinkers be “misaligned with the emotional baseline” of mainstream society. He also explained his notion of “radical hope,” his trust that “from the bottom [meaning those not in power] will the genius come that makes our ability to live with each other possible.”[12] I see that emotional baseline as dreaming of a progressive settler state. Tippet, the interviewer, then recounted Díaz ’s idea that “all the fighting in the world will not help us if we do not also have hope, which is not blind optimism, but radical hope. Talk about what that is…” she said. Díaz responded: I do trust in the collective genius of all the people who have survived these wicked systems. I trust in that. I think from the bottom will the genius come that makes our ability to live with each other possible. I believe that with all my heart. I have radical hope that settler relations based on violent hierarchies and concepts of property do not have to be all there is. This crisis or transition time in the US and Canada, and globally, offers an opportunity to cease cultivating a misplaced love for the state that insists on dreams of progress toward a never-arriving future of tolerance and good that paradoxically requires ongoing anti-blackness and genocidal violence. The path toward the supposed democratic promised land of settler mythology is in everyday life a nightmare for many around the globe. We require another narrative path to guide us. Indigenous people are proposing a relational web framework that is more about here and now, and not about when. We have an opportunity, if we choose to see it that way, to be misaligned with the emotional, intellectual, and (un)ethical baseline and narrative of those who hold power. We can have radical hope in a narrative that entails not redeeming the state, but caring for one another as relations. How do we live well here together? The state has and will continue to fail to help us do that.  I leave you with an inspirational quote from an Indigenous thinker who is misaligned with the emotional baseline of settler sexuality. At Converge Con last week, I interviewed Janet Rogers for the Media Indigena podcast I do every other week. Janet is a poet and performance artist who is Mohawk and wrote the book Red Erotic in 2010. There is a more Indigenous erotica coming out now, but Janet was a bit ahead of the curve perhaps. I mentioned to her that at Converge Con I felt like non-Indigenous people were more respectful and less invasive with their questions and their assumptions about my Indigenous perspective than is usually the case when I am in a largely non-Indigenous space. I thought their focus on consent culture might have a lot to do with their respectful behavior. Here is what she had to say: I’m … coming to the realization that the sensitivity, the consideration, the education, the awareness, the “awokeness”—if you will—within the sex positive community overflows into that awareness, sensitivity…into how those communities are relating to Indigenous people….Your practice and understanding of your own sexuality overflows into the rest of your life. That’s where it begins!...If you’ve got that resolved in the bedroom…all of that empowerment, all of that positivity is going to overflow in other areas of your life. I am taking her advice to heart. I am trying to get it right in the bedroom so I can get it right in the rest of my life. I think you are too. ---------------- NOTES *ACKNOWLEDGEMENT. Thanks to all of the people at Converge Con 2018 in Vancouver who I had the pleasure of thinking with over the weekend of April 7-8, 2018. Their sex positivity work in the world fertilized this keynote that I gave the following weekend, April 14, 2018, in Seattle. [1] http://www.convergecon.ca/about/. [2] Scott L. Morgensen . The Spaces Between Us: Queer Settler Colonialism an˙d Indigenous Decolonization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011: 23. [3] Scott Lauria Morgensen. “Settler Homonationalism: Theorizing Settler Colonialism within Queer Modernities,” GLQ: A Jouranl of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16(1-2) (2010), 106 [4] Katherine Franke. Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Inequality (New York: NYU Press, 2015). Also see Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and Nation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) and Sarah Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press 2008). [5] http://www.yesmagazine.org/issues/decolonize/white-allies-lets-be-honest-about-decolonization-20180403. [6] Morgensen 2011, 81. [7] For more on solo polyamory, check out these two-oft read articles. Aggiesez. “What is Solo Polyamory? My Take.” SOLOPOLY: Life, Relationships, and Dating as a Free Agent. December 5, 2014. Available at: https://solopoly.net/2014/12/05/what-is-solo-polyamory-my-take/. And Elisabeth A. Sheff. “Solo Polyamory, Singleish, Single & Poly.” Pyschology Today. October 14, 2013. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-polyamorists-next-door/201310/solo-polyamory-singleish-single-poly [8] David Delgado Shorter (2015). Sexuality. In The World of Indigenous North America. Robert Warrior (ed.). New York and London: Routledge: 487-505. [9] Shorter 2015, 490 and 497. [10] I have actually expanded the thinking on decolonization in this paragraph beyond what I spoke during the keynote. In editing this for the blog, I realized that I needed to explain my use of “decolonization” in this paragraph. I am still thinking through this use of decolonization so I welcome thoughtful thoughts from others who work with decolonial ideas in Indigenous Studies especially. [11] Shorter 2015, 497-8. [12] On Being with Krista Tippett. Interview with Junot Diaz. https://onbeing.org/programs/junot-diaz-radical-hope-is-our-best-weapon-sep2017/. September 14, 2017. (Retrieved February 11, 2018).

3 Comments

If I were a country music singer I’d write a song by the same title as this blog post. I would love to be an ethical nonmonogamist, sequin-sporting, cowboy boot wearing Native American country music star, belting out radically different narratives of love, lust, and loss. Steel guitar and fiddles would scream behind me. But I digress.

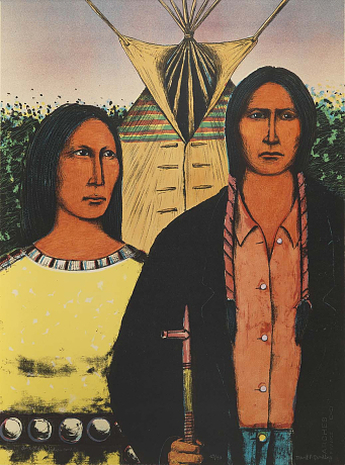

I left a state sanctioned legal marriage in 2010, or so I thought. We have never legally divorced. I don’t care about the legalities. We are still financially and socially entangled as coparents, and we occasionally collaborate professionally. I don’t plan on marrying again. I will always be responsible financially to my coparent’s wellbeing, if he needs me to be. He has been my closest friend. There are also benefits to being legally married in the US, that settler state of which I am a citizen and where my coparent still resides with our child. The US denies its citizens universal healthcare and makes it difficult for “alternative” families (i.e. not heterosexual and/or monogamous) to enjoy rights of visitation in hospitals, or easier child custody arrangements. Legal marriage, including same-sex marriage, helps deliver these benefits. Marriage can also provide tax benefits, cheaper insurance and other financial incentives. Living in two separate households is expensive enough. The financial perks of remaining legally married help even though I now feel deeply negative about the institution. Such benefits should not be reserved for those who are coupled in normative, monogamous unions constituted along with legal marriage. But this powerful nationalist institution reserves for itself the utmost legitimacy as an ideal social form, one we are all supposed to aspire to or we are marked as deviant. It asserts its centrality at the heart of a good family. It forecloses other arrangements and choices. Even after I tried to abandon settler marriage, it continues to break my heart year after year as I struggle to live differently in a world so fundamentally conditioned by it. I wrote in a July 2014 blog post, Couple-centricity, Polyamory and Colonialism, about this form of relating and how it was imposed to build the white nation and decimate indigenous kin systems. The diverse ways of relating of other marginalized peoples, e.g. formerly enslaved African-Americans post-emancipation and their descendants, LGBTQ folks, and those from particular religions that advocate plural marriage (my readers may have less sympathy for the latter) have also been undercut by settler norms of sexuality and family.[1] The High Cost of Resisting Compulsory Monogamy In 2010, I was still brainwashed by compulsory monogamy. I was deeply pained by not feeling what I thought I was supposed to feel in a lifelong, coupled relationship. I thought if I found the “right” monogamous relationship my confusion and pain would be no more. But I did not entertain that idea for long in the separation. I cannot honestly remember why I decided to explore ethical nonmonogamy, at first by reading, and then by actively engaging with an ethical nonmonogamy community in the city I moved to. In the several years since I began living as a nonmonogamist, I have climbed a steady learning curve. Many of those lessons are documented in this blog. But despite my realization that settler sexuality and family are the source of much anguish for me, for my extended family in our mostly “failures” to attain it, and for indigenous peoples more broadly, I have consistently known that if I could go back in time to 1997, I would get married all over again. We brought our daughter into this world. I would change nothing if it meant she would not be here. Being the cultural person I am, I live according to the idea that there is a purpose that I will probably never fully name to our daughter’s presence in this world. I cannot imagine this world without her. I would do every single thing exactly the same in order to make sure that she arrived in this world exactly the person she is, both biologically and socially. I understand those aspects as co-constitutive. That is, we are biosocial beings. But even aside from our daughter, I would get married all over again. Had we not legally married he would have moved overseas without me for a once-in-a-lifetime job opportunity, and that would have ended our relationship. We had to be legally married, according to immigration, for me to accompany him long-term. I would marry him all over again because I grew enormously with him. I don’t know if he would say the same. I hope so. If he would not, that would be sad. We spent so many years together. My daughter’s father is someone with whom I have always questioned my cultural and emotional fit. He is not a tribal person. Those are the people I connect emotionally most deeply with. Yet he and I have a deep and abiding intellectual and political fit, and I have not been able to let that go. We never ever lack for ideas to discuss together, and with such animation. We think and write well together. We are highly intellectually complementary, and that matters to us since we both do intellectual work. Physically we are a good match as well, except for me sometimes when the cultural connection felt not enough, when I especially longed for that kind of emotional intimacy, and which no doubt I did not provide for him either. There are things I will never understand about him. I attribute that to our very different cultural upbringings. I would grow detached, retreat physically. I eventually accepted that he was not the right one. Yet I see why I got together with him, and why I kept coming back after several attempts early on to leave, why I ended up staying so long. And yet I also cannot regret leaving. I simply don’t see how I could have done anything differently given who I was, and who he was each step of the way. I did not take the easy way out. I tried hard for years to understand. It was only through staying, and then finally leaving, and then studying and practicing ethical nonmonogamy that I came to understand the structures that produced our relationship, and which continue to. I know that there was no other choice but to eventually leave. I have revisited this decision many times. Each recollection, I arrive at the same conclusion. The unhappiness was growing too large. My behavior in the marriage too deteriorated. I grew to dislike my coparent and myself more every day. I had liked us both when we got together. I finally couldn’t live like that. I had respected us both. I wanted to respect us both again. I had so much to change. I see many couples out in the world mistreating one another, or suffering in silence. Between my own marriage and the nonmonogamous relationships I’ve been in, both with divorced people and with those attempting to make their marriages work, I know how pervasive are unmet needs, the resentments and sadness that come for so many with compulsory monogamy. I see these dynamics everywhere now. And I no longer see them as individual failings. For many people, there are few real choices. Our society does not want to accommodate anything but compulsory monogamy. It insists on the right one, until death do you part, settling down as a mark of maturity, making a commitment with a narrow definition of what that looks like. Society then stigmatizes multiple needs and vibrant desire as commitment phobia, wanderlust, sordid affairs, promiscuity, cheating. Indeed, our society better accommodates lying than it facilitates openness and honesty. While I am able to choose not to lie, to be openly nonmonogamous with my partners, it has come at a significant emotional and financial cost to all involved when I left a normative marriage to eventually figure it out. Only if I were who I am now could I have made a gentler, wiser choice six years ago. Only if I were an ethical nonmonogamist then could I have tried to make another decision, and asked my coparent to join me in that. He is an anti-racist, anti-colonial, sex-positive feminist. Chances are he would have tried. But I was not who I am now. It was an intensive, committed journey to get here. I also know long-together couples in open relationships who work well, who love and respect each other and their other partners, and whose children are well taken care of. Ethical nonmonogamy, if it were a legitimate social choice that we were taught early on, like we are taught compulsory monogamy from our first consciousness, would enable more expansive notions of family thus keeping families more intact. I probably would not have left. I would have known then that no one partner, even a culturally more familiar one, could provide all I need. A different kind of marriage is a marriage I can probably get behind. This is one reason, despite my misgivings about the Marriage Equality movement, I do think queers getting married will trouble our mononormative conceptions of marriage as part of their critiques of heteronormative marriage. Queers more often do ethical nonmonogamy. If anyone is going to marry, better queers than straights in my opinion. Crying the Nights into a Coherent Narrative Six years into this transition, I have begun crying myself to sleep each night, either at the beginning of the night, or sometimes in the middle. I never sleep the night through. My tears do not represent regret. They mourn ongoing, inevitable loss. Crying is like composing, whether words, or song, I imagine. I let the nightly cries take me as if they are a spirit possession so strong it is easier to submit. I work through them as hard forgings of language that are at first raw, then sensical, poetic. It is a form of intellectual intercourse with the emotions of my body, with history, with the planet and skies. My days are bright and pass quickly with vibrant intellectualism—with measured hope in an era where many have little. Why then are the nights so hard? After much pondering, I think I know. The nights this far north are expansive in their starry blue-blackness. And though they grow shorter, squeezed on both ends by sun, they are somehow not smaller. The night relinquishes no power. History and auto-ethnographic data flood in to widen the hours of unsleeping. Until finally I fall asleep without realizing. I am not a person who can live content without understanding. I was deeply troubled in a normative marriage. In order to change anything, I had to understand why. It took me six years of active study of myself, of texts, of others to understand. During the last few months, in the long nights of reflection and in deeply physical bodily mourning, I have come to know that I could have done nothing differently. Under the weight of settler history, I had a narrow range of choices. Of course I do not feel blameless. My love and longing for my daughter won’t allow that. My nightly cries have now become simple mourning of every night lost with her—every night that I cannot hug her goodnight, or rub her back until she falls asleep. She is a teenager now but like all of the children in our extended family, she likes to sleep with her mom. I mourn the loss of cooking dinner with her in the evenings, her chatter in the kitchen, her eagerness to learn how to cook. I mourn her beautiful singing voice daily, seeing the progress of her paintings weekly in the art studio. I miss giggling and plotting and whispering with her in person. I left a marriage that her father had a much easier time fitting into. Settler marriage was a model that more or less worked in his life experience. He was always her primary caretaker. I could never have asked to take her with me, not then anyway. I also left for a nonhuman love it turns out, although that took me a while to realize. I needed to be back on the vast North American prairies. My coparent loves living near the sea. While I am fed by multiple partial human loves I cannot do without that land-love. So I am thankful for Skype. I am thankful for jet planes. I am thankful that I mostly have the means to make this work. But the distance cuts hard, especially in the middle of the universe of night when I am far from my daughter, when I hear matter-of fact thoughts in the crystal quiet: Things might not end well. There are no guarantees. Yet maybe “ending well” is a vestige of monogamy, a vestige of the utopic but destructive ideal of settlement in its multiple meanings: not moving or transitioning; settling for the best thing we can imagine; closure, no open doors. But a life in which our child lives long plane rides away from one or the other parent seems a sad alternative to the settler monogamy and marriage I cannot abide. So much travel feels ultimately unsustainable—emotionally, financially, and environmentally. I think of refugees of war, or economic migrants who live through different sets of oppressive circumstances half a world away from their loves, both human and land. I try not to feel sorry for myself. I still have so much. I try to have faith that I can keep patching together my loving relations over an arc of the globe for as long as I need to. I try to have faith in new ways of knowing and being, ways that scare me. I am in uncharted territory. I hope I can keep going. Maybe something will change. Ethical Nonmonogamy as a Site of Biocultural Hope Settler marriage, sexuality, and family have been cruel and deep impositions in my people’s history, and in mine. My ancestors lived so differently. I think we tribal peoples are left with pieces of foundations they built. What we have been forced, shamed, and prodded into building in their place is an ill fit. But it is not like we have plans or materials to build as our ancestors did. We go on as best we can with what we have. My ancestors had plural marriage, at least for men. And from what I read in the archives “divorce” was flexible, including for women. Women controlled household property. Children were raised by aunts, uncles, and grandparents as much or more than by parents. The words in my ancestors’ language for these English kinship terms, and thus their roles and responsibilities, were cut differently. I know one feminist from a tribe whose people are cultural kin to mine who speculates that maybe the multiple wives of one husband may sometimes have had what we call in English “sex” with one another. (I assume when they were not sisters, which they sometimes were.) And why not? In a world before settler colonialism—outside of the particular biosocial assemblages that now structure settler notions of “gender,” “sex,” and “sexuality,” persons and the intimacies between them were no doubt worked quite differently. Much of the knowledge of precisely how different they were has been lost. Oppression against what whites call sexuality has been pervasive and vicious. Our ancestors lied, omitted, were beaten, locked up, raped, grew ashamed, suicidal, forgot. We have inherited all of that. I live and work in pursuit of new ways of loving, lusting, and losing amidst the ruins and survivals together of my ancestors’ ways of relating. I work with what is left to work with. I take note of the historical accounts we retain, both in academic English and in our oral histories. I look to articulate these partial understandings with my lived experience in tribal community and the fundamental ethical lessons I’ve inherited from my people. Even in the instances where specific knowledge of cultural practices was beaten and shamed out of our peoples, I believe that we have retained in community fundamental ethical orientations to the world that can help us learn to love and relate in the 21st century in ways that are less conditioned by the specific settler structures of sex and family against which I live and write. Some of these ethical orientations include a sense of agnosticism about what we know and withholding judgment, a humility and patience to wait for more information; a sense of relatedness to other living beings rather than fundamental rights to own or control; a broader and less hierarchical definition of life (born of that agnosticism) than Western thinkers have tended to allow; a sense of being in good relation that is measured by actual relating rather than by doctrine; and finally not simply tolerance for difference but genuine curiosity about difference, and sometimes even delight in it. In my loving and relating, I look for and seek to proliferate “sites of biocultural hope” as my colleague and friend Eben S. Kirksey describes them. In what has been dubbed an anthropogenic age, in which humans have developed the capacity to fundamentally alter the Earth’s climate and ecosystems, Kirksey advocates something more than apocalyptic thinking. He is one of the non-indigenous thinkers with whom I am most in conversation. He encourages us to understand surprising, new biosocial formations in an era of environmental, economic, and cultural crisis as legitimate flourishings, and not simply deviance. Where Kirksey refers to "emergent ecological assemblages—involving frogs, fungal pathogens, ants, monkeys, people, and plants," I do not forget such other-than-human relations. But I also refer to indigenous peoples and cultures in the wake of American genocide as not only sites of devastation, but as sites of hope. My particular people have been post-apocalyptic for over 150 years. For other indigenous peoples it has been longer. Still, our bodies and continuing/emergent practices are ecosocial sites and manifestations of hope. We survive, even sometimes flourish, after social and environmental devastations, after and in the midst of settler cruelties from extermination to assimilation designed to wipe us from this land. I see us combining our fundamental cultural orientations to the world with new possibilities for living and relating. We’ve been doing this collectively in the Americas for over five centuries. We’ve done it with respect to syncretic forms of religion and ceremony, with dress, music, language, art and performance. Why should we not also articulate other ways to love, lust, and let love go? Settler love, marriage, and family in hetero- homo- and mononormative forms does not have to be all there is. I have to have faith in that. I am only beginning to imagine. Yours, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Katherine Franke. Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Equality (New York: NYU Press, 2015). Also see Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and Nation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) and Sarah Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press 2008).  THE INTERNET 2015 www.opte.org (Critical Poly interpretation: everything is related) THE INTERNET 2015 www.opte.org (Critical Poly interpretation: everything is related) Despite the fact that the polyamorous community says it over and over again—polyamory is ‘not just about sex’—the monogamously inclined media…cannot get past the fact that sex is a potential component in several relationships. Yet polyamory is by definition ‘many loves’. Sex might be a component and it also might not be….Mainstream media perception and focus on sex as the principle driver of polyamorous relationships, is not only incorrect, but it has damaged the real meaning of polyamory to such a[n] extent that I don’t know whether we can recover the word. Louisa Leontiades “The Mass Exodus of Polyamorous People Towards Relationship Anarchy" Postmodernwoman.com (October 5, 2015) There are many insightful blogs being written on topics that can be understood as “critical” polyamory. They contain analyses that go beyond more common treatments of emotional and logistical troubles related to having multiple, open relationships. Critical poly accounts address complex intersectional politics that condition how we are able to (or not) love openly and promiscuously. (See a selection of such blog posts on my links page.) And when I use the word promiscuous I do not define it as is standard in our mononormative, sex negative culture, i.e. as indiscriminate and random sexual encounters. Rather I re-define “promiscuous” as follows: PROMISCUOUS, adj. and adv. (OLD DEFINITION) Pronunciation: Brit. /prəˈmɪskjʊəs/ , U.S. /prəˈmɪskjəwəs/ Done or applied with no regard for method, order, etc.; random, indiscriminate, unsystematic. OED Third Edition (June 2007) PROMISCUOUS (NEW DEFINITION) Plurality. Not excess or randomness, but openness to multiple connections, sometimes partial. But when combined, cultivated, and nurtured may constitute sufficiency or abundance. Polyamory and Relationship Anarchy I am edified by what I see as an increase in critical polyamory analyses that address questions such as how can we participate in open relationships as persons conscious of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, disability and other kinds of privilege and marginality. How do we do polyamory in less hierarchical rather than more hierarchical ways? The more rule-bound and couple-centric forms of polyamory, for example, that privilege the (state sanctioned) married, cohabiting, child-sharing couple as “primary,” with additional relationships being “secondary,” seem to me to replicate many of the conditions of monogamy that I find politically and ethically distasteful. I am always interested in analyses that help us envision ways of relating beyond such normative arrangements and beyond Western notions of romantic “love” conditioned—whether we know it or not—by capitalism’s coercive power. I am an indigenous critic of “settler sexuality,” that is hetero- and homonormative forms of “love,” “sex,” and marriage. Or as Scott Morgensen—whose work established the term—defines it: “a white national heteronormativity [and increasingly also homonormativity] that regulates Indigenous sexuality and gender by supplanting them with the sexual modernity of settler subjects”.[1] In thinking against forms of settler sexuality, I have become intrigued by the concept of “relationship anarchy” (RA). I’ve read several recent online analyses of this term, including one by well-known poly blogger Louisa Leontiades, as a reorienting concept for previously identified polyamorous people. Leontiades, author of The Husband Swap (2015), references blogger Andie Nordgren’s “Short Instructional Manifesto for Relationship Anarchy,” and describes RA as follows: Relationship Anarchy is a relationship style characterised most often by a rejection of rules, expectations and entitlement around personal relationships. Relationship Anarchists are reticent to label their relationships according to normative expression (boyfriend, girlfriend etc.) believing these labels to be inherently hierarchical but rather look at the content of the individual relationships allowing their fluidity to evolve naturally under the guiding principles of love, respect, freedom and trust. Relationship Anarchy does not predefine sexual inclination, gender identity or relationship orientation. I am curious about and moved by the concept of “relationship anarchy” (RA). But anarchist thinkers such as the blogger at Emotional Mutation have pushed back against poly folks appropriating the term “relationship anarchy” to help us lessen the perceptional baggage generated when mainstream media presents our relationships simplistically with a “salacious hyperfocus on sexuality.” Emotional Mutation clearly differentiates RA from poly, when they explain that polyamorists will tend to avoid or reject “some of the more radical/anarchic avenues of non-monogamy” that Relationship Anarchist’s pursue. For example: …Relationship Anarchy rejects all arguments for policing the behavior of one’s intimate partners. ALL of them. What this means in practice is not only No “Agreements” in our own relationships, but also no participation in policing the rules/agreements/contracts of other peoples’ relationships. In other words, Relationship Anarchists are not necessarily anti-cheating. These descriptions of the RA ethic make a lot of sense to me after three years as an ethical nonmonogamist, one who has made an intensive intellectual and political project out of the practice. As I wrote in my last blog post, “Critical Polyamory as Inquiry & Social Change” (Dec. 13, 2015), I lament cheaters far less than I used to. Rather, I lament the society in which the concept of cheating has so much salience and causes so much pain. “Cheating” is an idea conditioned by what are ultimately ideas of ownership over others’ bodies and desires. Having been "cheated on" long ago before I was married, having been the unwitting dalliance of someone who was cheating, and having myself cheated out of confusion and resistance (I see now) to monogamy, I can say that I cannot tolerate lying. It insults my intelligence. I could not myself carry lies. I confessed quickly. Sometimes the truth hurts, but for me lying hurts more. Cheating comes in part from thinking that lying will hurt less than honesty. Indeed, for some it does hurt less. This is the reality of a compulsory monogamy society in which there are severe social, legal, and economic penalties for breaking the monogamous contract. Those of us who have had the wherewithal to say “I want out” know well those penalties. But the main reason that Relationship Anarchy intrigues me is my growing distaste—other than consent and safe sex agreements, of course—for relationship rules broadly. Like monogamy, I see fundamental aspects of polyamory to also involve imposing onto relationship categories and rules forged historically to manage society in hierarchical ways and which facilitate the coercive work of colonial states that always privilege the cultures and rights of whites over everyone else, the rights of men over women, and the rights of the heterosexuals over queers. Of course, state-sanctioned, heterosexual, one-on-one, monogamous marriage is tied to land tenure in the US and Canada, and helped bring indigenous and other women more fully under the economic and legal control of men. Polyamory only partly challenges settler sexuality and kinship, including marriage, in seeing ethical love as not being confined to the monogamous couple. But as I’ve written in an earlier blog post, “Couple-Centricity, Polyamory, and Colonialism” (July 28, 2014), it still often in practice privileges the married couple as primary, other relationships as secondary, and continues to invest in couple-centric and often nuclear forms of family that are deeply tied up with colonialism. Ethical nonmonogamy in the US and Canada does not do enough to question these settler forms of love, sexuality and family. Although to be sure, there are ethical nonmonogamists who do their best to loosen the strictures of settler family forms to the greatest degree they can in a society whose laws thwart alternative families, including indigenous and queer families, at every turn. Dyke Ethics and an Indigenous Ethic of Relationality In addition, and not unlike monogamists, nonmonogamous people also often privilege sexual relating in their definitions of what constitutes ethical nonmonogamy, or plural loves. Might we have great loves that don’t involve sex? Loves whom we do not compartmentalize into friend versus lover, with the word “just” preceding “friends?” Most of the great loves of my life are humans who I do or did not relate to sexually. They include my closest family members, and also a man who I have had sexual desire for, but that is not the relationship it is possible for us to have. I love him without regret. We have never been physically intimate. Is this somehow a “just” friends relationship? I do not love him less than the people I have been “in love” with. Might we also not have great and important loves that do not even involve other humans, but rather vocations, art, and other practices? I am coming to conceive of ethical nonmonogamy in much more complex and fluid terms than even polyamory (yet another form of settler sexuality) conceives of it. There are certain queer relationship forms that my evolving vision of relating resonates more closely with. In her forthcoming book, Undoing Monogamy: The Politics of Science and the Possibilities of Biology,[2] University of Massachusetts feminist science studies scholar Angela Willey articulates a broader sense of the erotic than is reflected in both monogamist and ethical nonmonogamist (i.e. polyamorist) sex-centered ideas of relating. Briefly, Willey defines the erotic in conversation with black lesbian feminist writer Audre Lorde and her idea of joy, “whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual.” Joy can involve humans and nonhumans, including entities and concepts not considered to be alive in a typical Western framework. The sexual and the romantic may be present in Lorde’s and Willey’s concept of the erotic, but they have no special status as a form of vital connection. Music, love of one’s work, satisfaction in building something, making love to another human being, artistic expression—all bring joy and fulfillment and are forms of eroticism. This can help us envision more expansive forms of connection and belonging beyond those produced by monogamy and nonmonogamy, and their sex centered understandings. Not that sex isn’t great for many of us, but it’s not been great for everyone. Nor do some people care to have what we call “sex.” Not all loves involve sex, even between partners. That should not diminish the veracity of love, commitment, and relating when it is the choice of both/all partners to not include sexual relations. The concept of erotic at play here does not hierarchize relationships according to the presence of sex, or the kind of sex. Willey is especially attuned to the loves and relating of queer subjects, “dykes” in particular, in whose circles she reads deep values of friendship, community, and commitments to social justice. And while sex and coupledom are present they are not uniquely centered. Willey’s observations are complementary to what I am calling an “indigenous ethic of relationality.” I am working to articulate a conceptual framework of relating with not only my human loves—sexual and not, but also with indigenous place, and with different knowledge forms. What is “Love” Anyway? Becoming (Partially) Together? All of this musing on plural, expansive mutual caretaking relations brings me back to this concept of “love,” which we throw around a lot in English. Since I moved 2400 miles north to Canada from the American south last summer and left behind a wonderful friend and lover—FB (short for Firefighter Boyfriend), I’ve had time to reflect on our way of relating for the 14 months we were in close contact. FB models the kind of relatedness—a kind of “love” one could call it—that I am moving toward. It is not quite polyamory, nor Relationship Anarchy. I don’t yet have a name for it. FB is always there for me, even when he is not here. We never saw each other more than once every 2-4 weeks, usually for a weekend at a time. But I saw him enact a kind of distributed web of faithfulness that is rare, at least in US American culture. FB attends to his many loves: his children, his parents and sibling, sometimes his previous lovers. He attended to me and to M and to R, his other partners during our time together. He attends to his athletic training partners. He attends to his friends since childhood. He attends to his work, which he takes very seriously. He attends to these people and practices with his heart and his physical being. He does work for people as part of attending to their complex human needs. He fixes cars, fixes things around the house, and for a few of us he attends to our bodies in sexual ways. He continues to check in with me though we are separated by thousands of miles. He even checks in with my child occasionally. I will always remember the day he accompanied us to a speaking gig I had in a town 100 miles from home. He tied his camping hammock from a tree on the university campus, and my child swung in it while FB played guitar and sang Johnny Cash songs to her so she wouldn’t have to be bored at my talk. He is filled with energy to attend to his many relations. While he helps nourish community far beyond his nuclear family, his children too are raised in community, with not only him but by extended family. I remain in relation with FB, although often now by messaging or Skype. I continue to converse with him, to learn with him. He is not indigenous but he gets it—at least the human side of this ethic of relatedness, a 21st century articulation of “all my relations,” that I work to live. I never told FB that I loved him. I was still defining love when we were together in the same city according to a couple-centric, probably more escalator-like definition, which FB and I were not ascending. Monogamous conditioning is probably like an addiction in that one must always be vigilant to its hunger, its willingness to help one cope or make sense of life. Though I work daily to gain nonmonogamy skills and to put down long- conditioned monogamous responses, I accept that it may always live inside me. I need the support of other nonmonogamous people who like me are in recovery from a colonial form of monogamy. Because I keep working at it, I am more skilled than I was a year ago in spotting monogamous responses in myself. I see that I was mistaken when I did not tell FB that I love him when I saw that I had his consent to share those words. In fact, we were enacting it even then. I understand now that love is not only feeling, but attention and willingness to caretake, even partially. Sometimes this includes sex. Sometimes it does not. From here on out, I will be more careful and thoughtful, yet more generous in my use of the word “love.” When we caretake, it must also include ourselves. FB attends to himself. He knows that he needs to replenish. He is also not afraid to ask others to attend to his life. Being in relation requires doing and asking. This is because we cannot do everything for ourselves, or for others. As tireless as FB often seems in his efforts to be in relation, he is also always clear that he cannot be everything to anyone. Along with him I learned that faithful attention to one’s loves requires not submitting to the myth that partners can “complete” or make each other whole. I have come to think that asking for that is not fidelity, but betrayal of oneself and one’s lover(s), thus the point of a broad, strong network of relations. We can only manage the heavy work of sustenance in cooperation with one another. FB and I have engaged in what Alexis Shotwell (after Donna Haraway) calls a form of “significant otherness.” Haraway refers to “contingent, non-reductive, co-constitutive relations between humans and other species” as she theorizes more ethical human relations with and responsibilities to the nonhuman world. By co-constitutive, Haraway refers to how we shape and make one another. We become who and what we are together, in relation. Taking Haraway’s reformulation of “significant otherness” as also a way to “talk about valuing difference,” Shotwell applies this relational ethic to her own analysis of polyamory practice: “significant otherness points towards partial connections, in which the players involved are relationally constituted but do not entirely constitute each other.” She also draws on Sue Campbell’s analysis of “relational self-construction”—the ways in which “we are formed in and through mattering relations with others…how our practices of being responsive to others shapes the kinds of selves we are.” [3] How does this play out on the ground? Through specific relations with FB, for example, in concert with my intellectual relating with theorists cited here (Campbell, Haraway, Lorde, Morgensen, Shotwell, and Willey), and with indigenous ways of thinking relationality, I can now articulate “love” in a more complex and considered way than I had before. I have learned through nonmonogamy practice and reflection on that practice—aided by feminist, indigenous, and queer theorists—that one becomes together differently with different persons, phenomena, and knowledges. This happens on material and social levels simultaneously. Different bodies and desires fit together differently, thereby shaping different sexual practices and facilitating different sets of skills. New desires and pleasures (sometimes surprising!) are biosocially constituted. Different personalities and social ways of moving in the world help us partially re-socialize one another. With the aid of lovers past and present, including intellectual and other loves whose actual bodies play less to no part in our intimacies, we are ever becoming. I began writing this post before Valentine’s Day, but life interfered and it took me a while to get back to it. But in that spirit, I leave you with a blessing: May your loves and relations be many, and not caged within settler-colonial norms of rapacious individualism, hierarchies of life, and ownership of land, bodies, and desires. I hope that every day you are able to spend time with some of your loves, whoever they are and in whatever relationship form they take. I wish you health and connection in 2016. Yours, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Scott Lauria Morgensen. “Settler Homonationalism: Theorizing Settler Colonialism within Queer Modernities,” GLQ: A Jouranl of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16(1-2) (2010), 106 [2] Angela Willey. Undoing Monogamy: The Politics of Science and the Possibilities of Biology. London and Durham: Duke University Press, 2016 [forthcoming]. [3] Alexis Shotwell. "Ethical Polyamory, Responsibility, and Significant Otherness." In Gary Foster, ed. Desire, Love, and Identity: A Textbook for the Philosophy of Sex and Love. Oxford University Press Canada: Toronto (forthcoming October 2016), 7.  American Indian Gothic (1983) David P. Bradley American Indian Gothic (1983) David P. Bradley Several evenings ago I attended a class and conversation on open relationships at a feminist sex shop in an increasingly trendy area of my mid-Continent city. The class was for the open relationship curious, or beginners. Although I’ve been at this for about 19 months, I’m still a beginner. My fabulous fellow WOC (woman of color) sex educator friend, Divina, led the course. She also does community activism on a range of other social issues that entangle and go beyond topics of sexuality. In this largely white, middle-class poly community, where I shy away from poly group events because I feel like a cultural outsider, I willingly submit to Divina’s skilled, effusive, and politically sophisticated leadership. Like me, she thinks about the role of compulsory monogamy in propping up a heteronormative, patriarchal, and colonial society. I can jump right in with her—into the politically deepest part of a conversation on this stuff and she’s right there with me. Plus she’s got years more on-the-ground experience in open relationships than I do. This particular class was aimed at a more general audience, however, tackling issues that many Poly 101 classes do—namely handling jealousy and the kind of never-ending communication that is a hallmark of healthy polyamory. While the heightened racial and cultural diversity at this meeting was encouraging (yay feminist sex shop!), another cultural bias nonetheless loomed large at this event, which I will address in this blog. That is the couple-centric culture that pervades our city’s poly scene, and our broader society. Coupledom is often the foundational assumption that anchors many poly discussions. Topics for conversation at this class included WHY (open the “primary” relationship)? And then ground rules (for the couple) to consider: WHO (can and cannot be a candidate for an additional relationship—mutual friends? Exes)? WHAT (kinds of sex with others does the couple agree is okay)? You get the drift. As a “single poly” person I sat there feeling feisty and thinking “What, are we single polys just out here populating the world to sexually and emotionally serve individuals in couples?!” We get the “honor” of being on lists of appropriate partners, eligible “secondaries.” Or not? Our bodies and hearts and desires get to be the objects of couples’ rules about what’s allowed. Or not? It’s easy to feel ancillary in this type of poly scene, a sort of “snap on” component to a more permanent—a more legitimate—entity. No doubt many poly folks in primary relationships struggle against hierarchy between that primary relationship and outside relationships. After all, the structure of the couple allows only so much. The language of primary and secondary only allows so much! Even in a Poly worldview that seeks to undo so many of the repressions and exclusions of monogamy, the normativity of the couple itself goes unquestioned by far too many polys. Yet its primacy in our society is engendered of the same institutions and unquestioned values that produce the monogamy we resist. Like monogamy, the couple entity as central to the nuclear family is bound up with the sex negativity that poly people battle as we argue for and live lives in which sex and love are not viewed in such finite terms (although time certainly is) and thus not “saved” for only one other person. Like monogamy, the couple (especially when legally married), is legitimated and rewarded at every turn—U.S. health insurance eligibility, clearer child custody arrangements, tax filing benefits, and general public recognition and validation. In our society this type of arrangement is assumed as the logical end point, what we are all looking for or should be looking for. One of my favorite bloggers, SoloPoly, has an excellent post on this “relationship escalator” (the expected progression—first meeting, courtship, sex, presenting as a couple in public, intimate exclusivity, establishing a routine together, commitment defined by these steps, culminating in legal marriage that is supposed to last until one person dies). She also has a second related post on “couple privilege” and a guest post on couple-centric polyamory, which links to the Secondary’s Bill of Rights. I’m posting that one on my refrigerator! The fight for recognition of same-sex marriage also testifies to the pervasive couple-centricity of our culture. The dyad, for so long opposite sex and now increasingly also same sex, is portrayed as the fundamental unit of love and family. It is a key structure used to try and gain what should be fundamental human and civil rights for all of our citizens. I am reminded of biology textbooks that describe the gene as “the fundamental unit of life,” an instance of gene fetishism in which molecules come to stand simplistically for much more complex social-biological relations, for nature and nurture that actually shape one another in all kinds of interesting and unpredictable ways. In addition to genetic essentialism, we have in our culture couple essentialism. We fetishize the couple making it stand at the heart of love and family, which are actually the product of much more complex social-biological relations. The (monogamous) couple and narrower notions of family have a hard time containing and often sustaining the great complexity of relations that we humans feel and forge as we attempt to connect with one another throughout life. As with genes, I am not saying the couple produces only myths and master narratives. Like molecular sequences, there is sometimes beauty and profoundness in what the couple produces. But just as genes do not alone embody the enormity of “life” (despite the assertions of too many scientists and pop culture more generally) neither should the “couple” and its offshoot “nuclear family” embody in its most essential form the enormity of human love, physical desire, and family. A final note on same sex marriage: gays don’t always do marriage like straights expect them to—to give but one example of many, their greater acceptance of ethical non-monogamy. I see this as another upside of marriage equality in addition to it being the right thing to do for same sex couples. From this non-monogamist’s point of view it may help us revise marriage into a less repressive institution.