Critical polyamorist blog

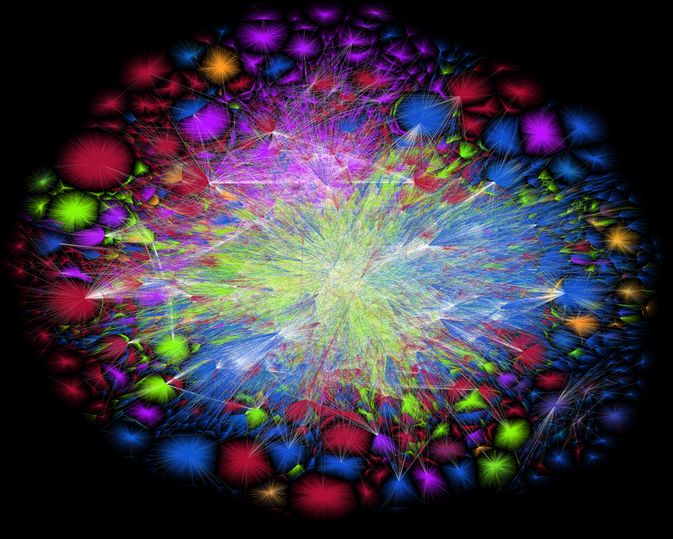

THE INTERNET 2015 www.opte.org (Critical Poly interpretation: everything is related) THE INTERNET 2015 www.opte.org (Critical Poly interpretation: everything is related) Despite the fact that the polyamorous community says it over and over again—polyamory is ‘not just about sex’—the monogamously inclined media…cannot get past the fact that sex is a potential component in several relationships. Yet polyamory is by definition ‘many loves’. Sex might be a component and it also might not be….Mainstream media perception and focus on sex as the principle driver of polyamorous relationships, is not only incorrect, but it has damaged the real meaning of polyamory to such a[n] extent that I don’t know whether we can recover the word. Louisa Leontiades “The Mass Exodus of Polyamorous People Towards Relationship Anarchy" Postmodernwoman.com (October 5, 2015) There are many insightful blogs being written on topics that can be understood as “critical” polyamory. They contain analyses that go beyond more common treatments of emotional and logistical troubles related to having multiple, open relationships. Critical poly accounts address complex intersectional politics that condition how we are able to (or not) love openly and promiscuously. (See a selection of such blog posts on my links page.) And when I use the word promiscuous I do not define it as is standard in our mononormative, sex negative culture, i.e. as indiscriminate and random sexual encounters. Rather I re-define “promiscuous” as follows: PROMISCUOUS, adj. and adv. (OLD DEFINITION) Pronunciation: Brit. /prəˈmɪskjʊəs/ , U.S. /prəˈmɪskjəwəs/ Done or applied with no regard for method, order, etc.; random, indiscriminate, unsystematic. OED Third Edition (June 2007) PROMISCUOUS (NEW DEFINITION) Plurality. Not excess or randomness, but openness to multiple connections, sometimes partial. But when combined, cultivated, and nurtured may constitute sufficiency or abundance. Polyamory and Relationship Anarchy I am edified by what I see as an increase in critical polyamory analyses that address questions such as how can we participate in open relationships as persons conscious of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, disability and other kinds of privilege and marginality. How do we do polyamory in less hierarchical rather than more hierarchical ways? The more rule-bound and couple-centric forms of polyamory, for example, that privilege the (state sanctioned) married, cohabiting, child-sharing couple as “primary,” with additional relationships being “secondary,” seem to me to replicate many of the conditions of monogamy that I find politically and ethically distasteful. I am always interested in analyses that help us envision ways of relating beyond such normative arrangements and beyond Western notions of romantic “love” conditioned—whether we know it or not—by capitalism’s coercive power. I am an indigenous critic of “settler sexuality,” that is hetero- and homonormative forms of “love,” “sex,” and marriage. Or as Scott Morgensen—whose work established the term—defines it: “a white national heteronormativity [and increasingly also homonormativity] that regulates Indigenous sexuality and gender by supplanting them with the sexual modernity of settler subjects”.[1] In thinking against forms of settler sexuality, I have become intrigued by the concept of “relationship anarchy” (RA). I’ve read several recent online analyses of this term, including one by well-known poly blogger Louisa Leontiades, as a reorienting concept for previously identified polyamorous people. Leontiades, author of The Husband Swap (2015), references blogger Andie Nordgren’s “Short Instructional Manifesto for Relationship Anarchy,” and describes RA as follows: Relationship Anarchy is a relationship style characterised most often by a rejection of rules, expectations and entitlement around personal relationships. Relationship Anarchists are reticent to label their relationships according to normative expression (boyfriend, girlfriend etc.) believing these labels to be inherently hierarchical but rather look at the content of the individual relationships allowing their fluidity to evolve naturally under the guiding principles of love, respect, freedom and trust. Relationship Anarchy does not predefine sexual inclination, gender identity or relationship orientation. I am curious about and moved by the concept of “relationship anarchy” (RA). But anarchist thinkers such as the blogger at Emotional Mutation have pushed back against poly folks appropriating the term “relationship anarchy” to help us lessen the perceptional baggage generated when mainstream media presents our relationships simplistically with a “salacious hyperfocus on sexuality.” Emotional Mutation clearly differentiates RA from poly, when they explain that polyamorists will tend to avoid or reject “some of the more radical/anarchic avenues of non-monogamy” that Relationship Anarchist’s pursue. For example: …Relationship Anarchy rejects all arguments for policing the behavior of one’s intimate partners. ALL of them. What this means in practice is not only No “Agreements” in our own relationships, but also no participation in policing the rules/agreements/contracts of other peoples’ relationships. In other words, Relationship Anarchists are not necessarily anti-cheating. These descriptions of the RA ethic make a lot of sense to me after three years as an ethical nonmonogamist, one who has made an intensive intellectual and political project out of the practice. As I wrote in my last blog post, “Critical Polyamory as Inquiry & Social Change” (Dec. 13, 2015), I lament cheaters far less than I used to. Rather, I lament the society in which the concept of cheating has so much salience and causes so much pain. “Cheating” is an idea conditioned by what are ultimately ideas of ownership over others’ bodies and desires. Having been "cheated on" long ago before I was married, having been the unwitting dalliance of someone who was cheating, and having myself cheated out of confusion and resistance (I see now) to monogamy, I can say that I cannot tolerate lying. It insults my intelligence. I could not myself carry lies. I confessed quickly. Sometimes the truth hurts, but for me lying hurts more. Cheating comes in part from thinking that lying will hurt less than honesty. Indeed, for some it does hurt less. This is the reality of a compulsory monogamy society in which there are severe social, legal, and economic penalties for breaking the monogamous contract. Those of us who have had the wherewithal to say “I want out” know well those penalties. But the main reason that Relationship Anarchy intrigues me is my growing distaste—other than consent and safe sex agreements, of course—for relationship rules broadly. Like monogamy, I see fundamental aspects of polyamory to also involve imposing onto relationship categories and rules forged historically to manage society in hierarchical ways and which facilitate the coercive work of colonial states that always privilege the cultures and rights of whites over everyone else, the rights of men over women, and the rights of the heterosexuals over queers. Of course, state-sanctioned, heterosexual, one-on-one, monogamous marriage is tied to land tenure in the US and Canada, and helped bring indigenous and other women more fully under the economic and legal control of men. Polyamory only partly challenges settler sexuality and kinship, including marriage, in seeing ethical love as not being confined to the monogamous couple. But as I’ve written in an earlier blog post, “Couple-Centricity, Polyamory, and Colonialism” (July 28, 2014), it still often in practice privileges the married couple as primary, other relationships as secondary, and continues to invest in couple-centric and often nuclear forms of family that are deeply tied up with colonialism. Ethical nonmonogamy in the US and Canada does not do enough to question these settler forms of love, sexuality and family. Although to be sure, there are ethical nonmonogamists who do their best to loosen the strictures of settler family forms to the greatest degree they can in a society whose laws thwart alternative families, including indigenous and queer families, at every turn. Dyke Ethics and an Indigenous Ethic of Relationality In addition, and not unlike monogamists, nonmonogamous people also often privilege sexual relating in their definitions of what constitutes ethical nonmonogamy, or plural loves. Might we have great loves that don’t involve sex? Loves whom we do not compartmentalize into friend versus lover, with the word “just” preceding “friends?” Most of the great loves of my life are humans who I do or did not relate to sexually. They include my closest family members, and also a man who I have had sexual desire for, but that is not the relationship it is possible for us to have. I love him without regret. We have never been physically intimate. Is this somehow a “just” friends relationship? I do not love him less than the people I have been “in love” with. Might we also not have great and important loves that do not even involve other humans, but rather vocations, art, and other practices? I am coming to conceive of ethical nonmonogamy in much more complex and fluid terms than even polyamory (yet another form of settler sexuality) conceives of it. There are certain queer relationship forms that my evolving vision of relating resonates more closely with. In her forthcoming book, Undoing Monogamy: The Politics of Science and the Possibilities of Biology,[2] University of Massachusetts feminist science studies scholar Angela Willey articulates a broader sense of the erotic than is reflected in both monogamist and ethical nonmonogamist (i.e. polyamorist) sex-centered ideas of relating. Briefly, Willey defines the erotic in conversation with black lesbian feminist writer Audre Lorde and her idea of joy, “whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual.” Joy can involve humans and nonhumans, including entities and concepts not considered to be alive in a typical Western framework. The sexual and the romantic may be present in Lorde’s and Willey’s concept of the erotic, but they have no special status as a form of vital connection. Music, love of one’s work, satisfaction in building something, making love to another human being, artistic expression—all bring joy and fulfillment and are forms of eroticism. This can help us envision more expansive forms of connection and belonging beyond those produced by monogamy and nonmonogamy, and their sex centered understandings. Not that sex isn’t great for many of us, but it’s not been great for everyone. Nor do some people care to have what we call “sex.” Not all loves involve sex, even between partners. That should not diminish the veracity of love, commitment, and relating when it is the choice of both/all partners to not include sexual relations. The concept of erotic at play here does not hierarchize relationships according to the presence of sex, or the kind of sex. Willey is especially attuned to the loves and relating of queer subjects, “dykes” in particular, in whose circles she reads deep values of friendship, community, and commitments to social justice. And while sex and coupledom are present they are not uniquely centered. Willey’s observations are complementary to what I am calling an “indigenous ethic of relationality.” I am working to articulate a conceptual framework of relating with not only my human loves—sexual and not, but also with indigenous place, and with different knowledge forms. What is “Love” Anyway? Becoming (Partially) Together? All of this musing on plural, expansive mutual caretaking relations brings me back to this concept of “love,” which we throw around a lot in English. Since I moved 2400 miles north to Canada from the American south last summer and left behind a wonderful friend and lover—FB (short for Firefighter Boyfriend), I’ve had time to reflect on our way of relating for the 14 months we were in close contact. FB models the kind of relatedness—a kind of “love” one could call it—that I am moving toward. It is not quite polyamory, nor Relationship Anarchy. I don’t yet have a name for it. FB is always there for me, even when he is not here. We never saw each other more than once every 2-4 weeks, usually for a weekend at a time. But I saw him enact a kind of distributed web of faithfulness that is rare, at least in US American culture. FB attends to his many loves: his children, his parents and sibling, sometimes his previous lovers. He attended to me and to M and to R, his other partners during our time together. He attends to his athletic training partners. He attends to his friends since childhood. He attends to his work, which he takes very seriously. He attends to these people and practices with his heart and his physical being. He does work for people as part of attending to their complex human needs. He fixes cars, fixes things around the house, and for a few of us he attends to our bodies in sexual ways. He continues to check in with me though we are separated by thousands of miles. He even checks in with my child occasionally. I will always remember the day he accompanied us to a speaking gig I had in a town 100 miles from home. He tied his camping hammock from a tree on the university campus, and my child swung in it while FB played guitar and sang Johnny Cash songs to her so she wouldn’t have to be bored at my talk. He is filled with energy to attend to his many relations. While he helps nourish community far beyond his nuclear family, his children too are raised in community, with not only him but by extended family. I remain in relation with FB, although often now by messaging or Skype. I continue to converse with him, to learn with him. He is not indigenous but he gets it—at least the human side of this ethic of relatedness, a 21st century articulation of “all my relations,” that I work to live. I never told FB that I loved him. I was still defining love when we were together in the same city according to a couple-centric, probably more escalator-like definition, which FB and I were not ascending. Monogamous conditioning is probably like an addiction in that one must always be vigilant to its hunger, its willingness to help one cope or make sense of life. Though I work daily to gain nonmonogamy skills and to put down long- conditioned monogamous responses, I accept that it may always live inside me. I need the support of other nonmonogamous people who like me are in recovery from a colonial form of monogamy. Because I keep working at it, I am more skilled than I was a year ago in spotting monogamous responses in myself. I see that I was mistaken when I did not tell FB that I love him when I saw that I had his consent to share those words. In fact, we were enacting it even then. I understand now that love is not only feeling, but attention and willingness to caretake, even partially. Sometimes this includes sex. Sometimes it does not. From here on out, I will be more careful and thoughtful, yet more generous in my use of the word “love.” When we caretake, it must also include ourselves. FB attends to himself. He knows that he needs to replenish. He is also not afraid to ask others to attend to his life. Being in relation requires doing and asking. This is because we cannot do everything for ourselves, or for others. As tireless as FB often seems in his efforts to be in relation, he is also always clear that he cannot be everything to anyone. Along with him I learned that faithful attention to one’s loves requires not submitting to the myth that partners can “complete” or make each other whole. I have come to think that asking for that is not fidelity, but betrayal of oneself and one’s lover(s), thus the point of a broad, strong network of relations. We can only manage the heavy work of sustenance in cooperation with one another. FB and I have engaged in what Alexis Shotwell (after Donna Haraway) calls a form of “significant otherness.” Haraway refers to “contingent, non-reductive, co-constitutive relations between humans and other species” as she theorizes more ethical human relations with and responsibilities to the nonhuman world. By co-constitutive, Haraway refers to how we shape and make one another. We become who and what we are together, in relation. Taking Haraway’s reformulation of “significant otherness” as also a way to “talk about valuing difference,” Shotwell applies this relational ethic to her own analysis of polyamory practice: “significant otherness points towards partial connections, in which the players involved are relationally constituted but do not entirely constitute each other.” She also draws on Sue Campbell’s analysis of “relational self-construction”—the ways in which “we are formed in and through mattering relations with others…how our practices of being responsive to others shapes the kinds of selves we are.” [3] How does this play out on the ground? Through specific relations with FB, for example, in concert with my intellectual relating with theorists cited here (Campbell, Haraway, Lorde, Morgensen, Shotwell, and Willey), and with indigenous ways of thinking relationality, I can now articulate “love” in a more complex and considered way than I had before. I have learned through nonmonogamy practice and reflection on that practice—aided by feminist, indigenous, and queer theorists—that one becomes together differently with different persons, phenomena, and knowledges. This happens on material and social levels simultaneously. Different bodies and desires fit together differently, thereby shaping different sexual practices and facilitating different sets of skills. New desires and pleasures (sometimes surprising!) are biosocially constituted. Different personalities and social ways of moving in the world help us partially re-socialize one another. With the aid of lovers past and present, including intellectual and other loves whose actual bodies play less to no part in our intimacies, we are ever becoming. I began writing this post before Valentine’s Day, but life interfered and it took me a while to get back to it. But in that spirit, I leave you with a blessing: May your loves and relations be many, and not caged within settler-colonial norms of rapacious individualism, hierarchies of life, and ownership of land, bodies, and desires. I hope that every day you are able to spend time with some of your loves, whoever they are and in whatever relationship form they take. I wish you health and connection in 2016. Yours, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Scott Lauria Morgensen. “Settler Homonationalism: Theorizing Settler Colonialism within Queer Modernities,” GLQ: A Jouranl of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16(1-2) (2010), 106 [2] Angela Willey. Undoing Monogamy: The Politics of Science and the Possibilities of Biology. London and Durham: Duke University Press, 2016 [forthcoming]. [3] Alexis Shotwell. "Ethical Polyamory, Responsibility, and Significant Otherness." In Gary Foster, ed. Desire, Love, and Identity: A Textbook for the Philosophy of Sex and Love. Oxford University Press Canada: Toronto (forthcoming October 2016), 7.

0 Comments

|

Photo credit: Short Skirts and Cowgirl Boots by David Hensley

The Critical Polyamorist, AKA Kim TallBear, blogs & tweets about indigenous, racial, and cultural politics related to open non-monogamy. She is a prairie loving, big sky woman. She lives south of the Arctic Circle, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can follow her on Twitter @CriticalPoly & @KimTallBear

Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|