Critical polyamorist blog

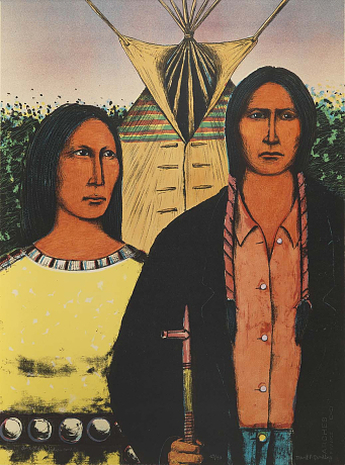

American Indian Gothic (1983) David P. Bradley American Indian Gothic (1983) David P. Bradley Several evenings ago I attended a class and conversation on open relationships at a feminist sex shop in an increasingly trendy area of my mid-Continent city. The class was for the open relationship curious, or beginners. Although I’ve been at this for about 19 months, I’m still a beginner. My fabulous fellow WOC (woman of color) sex educator friend, Divina, led the course. She also does community activism on a range of other social issues that entangle and go beyond topics of sexuality. In this largely white, middle-class poly community, where I shy away from poly group events because I feel like a cultural outsider, I willingly submit to Divina’s skilled, effusive, and politically sophisticated leadership. Like me, she thinks about the role of compulsory monogamy in propping up a heteronormative, patriarchal, and colonial society. I can jump right in with her—into the politically deepest part of a conversation on this stuff and she’s right there with me. Plus she’s got years more on-the-ground experience in open relationships than I do. This particular class was aimed at a more general audience, however, tackling issues that many Poly 101 classes do—namely handling jealousy and the kind of never-ending communication that is a hallmark of healthy polyamory. While the heightened racial and cultural diversity at this meeting was encouraging (yay feminist sex shop!), another cultural bias nonetheless loomed large at this event, which I will address in this blog. That is the couple-centric culture that pervades our city’s poly scene, and our broader society. Coupledom is often the foundational assumption that anchors many poly discussions. Topics for conversation at this class included WHY (open the “primary” relationship)? And then ground rules (for the couple) to consider: WHO (can and cannot be a candidate for an additional relationship—mutual friends? Exes)? WHAT (kinds of sex with others does the couple agree is okay)? You get the drift. As a “single poly” person I sat there feeling feisty and thinking “What, are we single polys just out here populating the world to sexually and emotionally serve individuals in couples?!” We get the “honor” of being on lists of appropriate partners, eligible “secondaries.” Or not? Our bodies and hearts and desires get to be the objects of couples’ rules about what’s allowed. Or not? It’s easy to feel ancillary in this type of poly scene, a sort of “snap on” component to a more permanent—a more legitimate—entity. No doubt many poly folks in primary relationships struggle against hierarchy between that primary relationship and outside relationships. After all, the structure of the couple allows only so much. The language of primary and secondary only allows so much! Even in a Poly worldview that seeks to undo so many of the repressions and exclusions of monogamy, the normativity of the couple itself goes unquestioned by far too many polys. Yet its primacy in our society is engendered of the same institutions and unquestioned values that produce the monogamy we resist. Like monogamy, the couple entity as central to the nuclear family is bound up with the sex negativity that poly people battle as we argue for and live lives in which sex and love are not viewed in such finite terms (although time certainly is) and thus not “saved” for only one other person. Like monogamy, the couple (especially when legally married), is legitimated and rewarded at every turn—U.S. health insurance eligibility, clearer child custody arrangements, tax filing benefits, and general public recognition and validation. In our society this type of arrangement is assumed as the logical end point, what we are all looking for or should be looking for. One of my favorite bloggers, SoloPoly, has an excellent post on this “relationship escalator” (the expected progression—first meeting, courtship, sex, presenting as a couple in public, intimate exclusivity, establishing a routine together, commitment defined by these steps, culminating in legal marriage that is supposed to last until one person dies). She also has a second related post on “couple privilege” and a guest post on couple-centric polyamory, which links to the Secondary’s Bill of Rights. I’m posting that one on my refrigerator! The fight for recognition of same-sex marriage also testifies to the pervasive couple-centricity of our culture. The dyad, for so long opposite sex and now increasingly also same sex, is portrayed as the fundamental unit of love and family. It is a key structure used to try and gain what should be fundamental human and civil rights for all of our citizens. I am reminded of biology textbooks that describe the gene as “the fundamental unit of life,” an instance of gene fetishism in which molecules come to stand simplistically for much more complex social-biological relations, for nature and nurture that actually shape one another in all kinds of interesting and unpredictable ways. In addition to genetic essentialism, we have in our culture couple essentialism. We fetishize the couple making it stand at the heart of love and family, which are actually the product of much more complex social-biological relations. The (monogamous) couple and narrower notions of family have a hard time containing and often sustaining the great complexity of relations that we humans feel and forge as we attempt to connect with one another throughout life. As with genes, I am not saying the couple produces only myths and master narratives. Like molecular sequences, there is sometimes beauty and profoundness in what the couple produces. But just as genes do not alone embody the enormity of “life” (despite the assertions of too many scientists and pop culture more generally) neither should the “couple” and its offshoot “nuclear family” embody in its most essential form the enormity of human love, physical desire, and family. A final note on same sex marriage: gays don’t always do marriage like straights expect them to—to give but one example of many, their greater acceptance of ethical non-monogamy. I see this as another upside of marriage equality in addition to it being the right thing to do for same sex couples. From this non-monogamist’s point of view it may help us revise marriage into a less repressive institution.

Of course it was not always so that the (monogamous) couple ideal reigned. In Public Vows: A History of Marriage and Nation, Nancy Cott argues with respect to the U.S that the Christian model of lifelong monogamous marriage was not a dominant worldview until the late nineteenth century, that it took work to make monogamous marriage seem like a foregone conclusion, and that people had to choose to make marriage the foundation for the new nation.” In The Importance of Being Monogamous, historian Sarah Carter also shows how “marriage was part of the national agenda in Canada—the marriage ‘fortress’ was established to guard the [Canadian] way of life.”[1] At the same time that monogamous marriage was solidified as ideal and central to both U.S. and Canadian nation building, indigenous peoples in these two countries were being viciously restrained both conceptually and physically inside colonial borders and institutions that included reservations/reserves, residential schools, and churches and missions all designed to “save the man and kill the Indian.” Part of saving the Indians from their savagery meant pursuing the righteous monogamous, couple-centric, nuclear-family institution. Land tenure rights were attached to marriage in ways that tied women’s economic well-being to that institution. Indeed, the nuclear family is the most commonly idealized alternative to the tribal/extended family context in which I was raised. As for many indigenous peoples, prior to colonization the fundamental indigenous social unit of my people was the extended kin group, including plural marriage. We have a particular word for this among my people but to use it would give away my tribal identification. With hindsight I can see that my road to ethical non-monogamy began early in my observations in tribal communities of mostly failed monogamy, extreme serial monogamy, and disruptions to nuclear family. Throughout my growing up I was subjected by both whites and Natives ourselves to narratives of shortcoming and failure—descriptions of Native American “broken families,” “teenage pregnancies,” “unmarried mothers,” and other “failed” attempts to paint a white, nationalist, middle class veneer over our lives. I used to think it was the failures to live up to that ideal that turned me off, and that’s why I ran for coastal cities and higher education—why I asserted from a very early age that I would never get married. Now I see that I was suffocating under the weight of the concept and practice of a normative middle-class nuclear family, including heteronormative coupledom period. I was pretty happy as a kid in those moments when I sat at my grandmother’s dining room table with four generations and towards the end of my great-grandmother’s life FIVE generations. We would gather in her small dining room with it’s burnt orange linoleum and ruffled curtains, at the table beside the antique china cabinet, people overflowing into the equally small living room—all the generations eating, laughing, playing cards, drinking coffee, talking tribal politics, and eating again. The children would run in and out. I would sit quietly next to my grandmothers hoping no one would notice me. I could then avoid playing children’s games and listen instead to the adults' funny stories and wild tribal politics. Couples and marriages and nuclear families got little play there. The collectives—both our extended family and the tribe—cast a much wider, more meaningful, and complexly woven net. The matriarch of our family, my great-grandmother, was always laughing. She would cheat at cards and tell funny, poignant stories about my great-grandfather who died two decades before. Aunts and uncles would contribute their childhood memories to build on those stories. My mother would often bring the conversation back to tribal or national politics. A great-grandchild might have been recognized for some new creative, academic, or athletic accomplishment. The newest baby would be doted on as a newly arrived human who chose this family. The Mom who might be 18 or 20 and unmarried would have help, and she would be told to go back to school, or find a career track to better her life for her baby. Too many in my family faced life choices more restricted than mine are now. Others were simply unwilling to sacrifice a life lived daily among extended family and tribe, as I have done. From where I stand it looks like my most of my extended family members have more security in that small town family and tribal community, or in the coherent, densely-populated “urban Indian” community in which I spent part of my childhood, than they do in Euro-centric traditions of nuclear family and marriage. On the other hand, my security and primary partnership is the educational and professional escalator that I ride and climb to ever more opportunities in high-up cities. Paradoxically, in seeking security outside of one colonial imposition—marriage and nuclear family (although I also tried that for a good while and wasn’t so skilled at it)—I chose a highly individualistic path that enmeshes me in different sets of colonial institutions: all of those corporate, nonprofit, government, and academic institutions in which I have worked. I also have a global indigenous and professional network that brings tremendous meaning to my life. But individuals among them are rarely here at night when I need someone to share words, laughter, food and touch with. I need to build some sort of extended kin group here in this city where I live. I doubt that coupledom (mine or others) combined with “outside” relationships will ever suffice in this context. Building something more collective is my desire and my challenge. Despite my focus on couple-centricity in Poly World, some polys refer to their intimate networks—their extended made families as “tribes.” But even those individuals are an ill fit for me for cultural reasons I’ve written about in earlier posts, ISO Feminist (NDN) Cowboys and Poly, Not Pagan, and Proud. I learn especially open communication lessons from Poly World, but I’ve made few real friends there. I look more to indigenous peoples for partial models, and I continue to seek non-indigenous people in this city who don’t fit the existing poly cultural mode, but who are committed to open relationships. Alas, it is exhausting being a minority within a minority. But I can never resist a challenge. One final insight: Indigenous colleagues that I admire speak and write of “decolonizing love,” for example the Nitâcimowin blog of University of Victoria graduate student Kirsten Lindquist (Cree-Métis). I obviously love her focus of decolonial analysis on relationships. It is a generative framework for pushing us to articulate a better world. But my slightly cynical aging self doesn’t quite believe that we can decolonize, meaning to withdraw from or dismantle colonialism. We live inside a colossal colonial structure that took most of the world’s resources to build. Does not every maneuver against colonialism occur in intimate relationship to its structures? There is no outside. Deep inside the shadows and shifting (cracking?) walls of that edifice I don’t anymore see my family’s and tribe’s failures at lasting monogamy and nuclear family as failure. I see us experimenting, working incrementally with tools and technologies that we did not craft combined with indigenous cultural templates in any open space we can find to build lives that make any sense to us at all. As ever, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and Nation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) in Sarah Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press 2008): 3-4.

17 Comments

My mother-in-law is dying. Even though her son and I are no longer together, she is still my mother-in-law. My co-parent, as we call each other now, is still my mother’s son-in-law. At least that is what my Native American mother says, and vehemently. I have no trouble with that. Just because Co-parent and I are no longer a monogamous romantic couple, does not mean that I do not want to remain his family. We raise a child together. We sometimes think and write together. We have been loquacious friends since the night we first met, and I hope we will continue to be. Until death do us part. In addition to being a stellar father to our child, a good son- and brother-in-law, he is a beloved uncle to my nieces and nephews--our nieces and nephews. We Natives—at least in my extended family and tribe—tend not to let white men’s laws and norms completely distort our thinking about family. That is not to say that we have been able to completely resist Eurocentric norms related to kin and marriage. Witness the politics of tribal enrollment in the United States in which our regulations governing who gets to be a tribal citizen have been informed for 100-plus years by curious Eurocentric notions of biogenetic kinship.[1] Our ancestors were also forced into monogamy by U.S. and Canadian state-builders who could not grant them full humanity without forcing indigenous people into heterosexual one-on-one, lifelong relationships, nuclearizing their families, attaching marriage to land ownership, and extending those notions of ownership to the women—the wives in whose name allotted lands were also given.[2] But in everyday practice, we are still adept at extended family. Beyond biological family, we also have ceremonies to adopt kin. And in my extended family we engage in a lot of legal adoption. This is aided by the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) that prioritizes the adoption of Native children by Native American tribal families so children have a better chance of remaining inside tribal cultures. In my opinion, we are culturally superior to the mainstream in the U.S. in our skills and values for making extended family. Not unlike this new practice of mine—polyamory (when it does not stop at sex and self-actualization, but goes farther to make family or community)—our tribal webs of kinship can be more emotionally, environmentally, and economically sustainable. Although like polyamory, the entanglements are demanding and it’s no bed of roses everyday. My mother-in-law and I were close. She always loved Native American art and took an interest in me right away when Co-parent first brought me home. I am not an artist of course. He would roll his eyes. He would lovingly tease her. For my part, I loved listening to her many stories and drinking wine together. She told me she loved having another woman around after raising only sons. And she was from the first moment thrilled with the coming of our child. The day she received in the post her birthday card with our positive pregnancy test folded inside, she left us a voice mail: “You have just lifted a dark cloud over my head!” She was so excited at our pregnancy. Her other grandchildren live half the world away. She too rarely sees them. Fittingly, our child is so much like my mother-in-law. Like Grandma, our child is an artist, and an animal lover. They share the same sense of color and abstractness in their painting. She doted on our child until she got Alzheimer’s. Even afterwards. When our child enters the Alzheimer’s unit, Grandma’s eyes light up. I have a difficult time with her passing. I do not mourn her dying. She did not want to live with dementia. I wonder if her spirit is trapped in her body and I want her to be free of that. Co-parent and our child and I agree: It is a blessing that Grandma is about to go to the spirit world. Although the thought crosses my mind that she has another capacity now. She looks with wonder at snowflakes and leaves twittering in wind, at miraculous birds. No, my difficulty is watching how my ex-husband’s Euro-American family greets death. Unlike in our tribe and family, they do not sit with their dying elder through the days and nights of the passing. First in the hospital for however long it takes, and then afterwards, a three-day wake. There is no tribe to bring food for the family. They do not tell stories for days punctuated by laughter, suddenly swallowed voices, silence, tears. Death like this at the end of a lived life is an event. We mark it, a bon voyage. I can bring none of this to my mother-in-law’s deathbed. While my tribal family still claims Co-parent as kin, familial terms are no longer forthcoming for me from his biological family. My rights are diminished and distance is what feels respectful while they mourn. My mother-in-law will likely die alone, outside the minutes of their daily visits. They are pained at her passing. They have a hard time watching her. I do not understand their relationship to death. She had a full life and for her generation of women, much more equality. She had children, a loving husband, an artistic path—her very own thing. Our child does not get to sit long enough with Grandma. The adults are too quick to leave. I hear she is in no pain. She goes peacefully. Why is coming to the end of a good journey unbearable to witness? Does the quieting of her vitality seem undignified, a failure? Death is too often construed as “giving up the fight.” After thinking hard on this, I conclude that a fundamental conceptual break conditions their relationship to death. Materiality is severed from spirit in their world. There is life and death. It is not only scientists who do this. Believers do too. The relationships are long and intimate between Western science and Christianity. There is no dichotomy in their shared conceptual-ethical framework that does not become hierarchy: life/death, human/animal, man/woman, civilized/savage. Death is bad because death ends life. They are afraid of death. In such a worldview, Earth and spirit do not touch. For some, there is no spirit, only earth. For others, Heaven is out there, the angels are holy and fly away. They don’t often know spirits to bridge worlds in mundane ceremonies, or in dreams. In their stories when spirits walk the planet, they are ghosts troubled and lost on their way to Heaven or diabolical and slipped through the cracks of Hell. But our spirits are persons—our social relations, wise or imperfect. Some were human. Some may be again. We tribal people don’t have scripture or a Google map plotting the streets of the spirit world. We don’t all share one named broker from this world to the next. We don’t pretend to know much. But we do know that death of the body opens up another stage of being. We have all seen or heard of it. We may not all have the same relations with spirits, but it is impossible to live in a tribal community and not live within a world where spirits do things. For us, materiality is part of beingness, not the other way around. With my mother-in-law’s passing, I am grateful again that I am a tribal person. I would not wish our Peoples’ hardships on anyone, but I would want no other life, no other body than that which is a product of their work in this world. Through colonization intimate relationships with our Peoples’ places of origin were disrupted. So much of indigenous peoples' self-determination in the U.S. (and Canada) is attempting to reconstitute those relationships with land, or just to live there. We attempt this in ethically impoverished political-economic systems, like washing filthy clothes in filthy water. But we also sustain our relations in non-material ways. Just as we do not relinquish the beingness of our human relatives with the passing of their biophysical bodies, we do not relinquish our relationships with our nonhuman relations in these lands, even after the legal, material, and scientific claiming of their bodies by nation states.  In the company of four generations I watched my great-grandmother breathe in and never again breathe out. A few hours later she visited her house. My aunt smelled her perfume wafting through the rooms. For twenty years she has visited me in dreams. I hold her rose-petal hands. I tell her I love her. As I age, I think of new questions to ask her. I hope my mother-in-law will visit our child in dreams. As our child grows older, the questions will come. Last night I said, “when you visit Grandma tomorrow, hold her hand, talk to her, tell her you love her. You never know what she might hear. Let her know she’s not alone.” Our child said with a “duh” tone and a shaking-back-and-forth head, “I know Mom. I promise. I was rubbing her head yesterday. I wanted to stay.” We fall to Earth into the hands of our ancestors. Why should we not leave it from beneath the touch of our descendants or our relations as they hand us back to ancestors again? As ever, The Critical (and ethnocentric) Polyamorist 8/20/14 Postscript: This bittersweet article, "Dead at noon: B.C. woman ends her life rather than suffer indignity of dementia," was published today in the Vancouver Sun. My mother-in-law (who, when she was still lucid) had expressed similar concerns as Gillian Bennett, the woman in the Sun story. My mother-in-law had also expressed the desire for options besides living with dementia in a completely incapacitated state. [1] David M. Schneider. American Kinship: A Cultural Account. Second Edition. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980 (1968). Also see Kirsty Gover, “Genealogy as Continuity: Explaining the Growing Tribal Preference for Descent Rules in Membership Governance in the United States,” American Indian Law Review 33(1) (2008): 243-309. Also see Kirsty Gover, “Genealogy as Continuity: Explaining the Growing Tribal Preference for Descent Rules in Membership Governance in the United States.” American Indian Law Review (33)1: 243-310. [2] Sarah Carter. The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 2008. During the past fourteen months of my iterative commitment to polyamory, one question occasionally troubles my mind for difficult hours. In the midst of my gratitude for what I have in a world of hardship and sorrow, I grow sad for a time and struggle with this predicament: Am I pursuing polyamory because I have given up hope of ever finding a person so compelling and compatible (and available and in the same country!) that we could remain committed to one another for the rest of our lives? This is the main question I return to time and again, and my chief struggle in polyamory. Am I taking the easy way out? Trying to avoid vulnerability? Disappointment? Commitment and compromise—the hard work of fidelity to another rather than just myself?

In the moments of struggle I also sometimes wonder if I am just too like my parents, neither of whom were able to sustain lifelong romantic partnerships. My life is richer with nurturing and opportunity than theirs were, but I share their propensity for travel and migration. They were both workaholics, both running from but also always returning home. I have come to see their migratory practices as not wholly dysfunctional but as a productive act of survival. And they just crave the road. So do I. Too bad poly wasn’t a viable choice for my parents in their non-privileged mid- to late-20th century middle America world. Maybe both of them would have had more success in love, felt less like failures or oddballs in that regard. Their serial monogamy and that of my extended family members over the course of decades did none of us much good. I saw more than my share of failed marriages and dysfunctional couple relationships. It is sad to remember so much unrealistic idealism and expectations that could never be fulfilled coupled with controlling, dishonest, and disrespectful behavior of men towards women, sometimes of women towards men, but most of all the collateral damage to the children involved. Our struggles were clearly shaped by oppressive colonial institutions that deeply damaged Native American families and communities for more than a century. I see now that there was little possibility of living up to the successful nuclear family ideal. On the other hand, despite colonization, we are still accomplished at cultivating networks of extended family—biological, adopted, and ceremonial—and that makes me proud. And it is probably a key reason that I find myself drawn to this non-Native American practice called polyamory. In its ideal form as I imagine it, poly can help build extended family that includes but goes beyond the restrictive bonds of biology. Whatever the history that brought me to here—whether it is family- or culture-specific, a result of colonial history, or a fundamental human condition (some like to argue that non-monogamy is biological nature), whether it is nature or nurture or both—every time I enter the space of struggle over poly versus monogamy, I walk out the other side still committed to polyamory. I am certain that even were I to find “true love” again (I think I’ve felt that at least twice in my life), I’d find myself back here in a few years, facing a choice to open that relationship. For I no longer believe that it is realistic or fair or ultimately loving to myself and to my partner to command that each of us legitimately long for and be only with one another. I am also coming to believe as I weigh healthy and honest monogamy against healthy and honest polyamory, neither is any more or less difficult. They both involve considerable emotional work, ethical commitment, the courage to be vulnerable, good communication skills, compassion and withholding judgment. In other words, neither set of practices, if they are to satisfy on multiple levels, allows us to slack. I must therefore decide how to live, love, and desire in the way that seems to best fit me, and I am fortunate to have the resources to do that. While my ethical and analytical head always chooses polyamory, my heart is still deeply conditioned by the romantic and illusory ideal of safety in monogamy. And my body wants what both can offer: connection. In this struggle, I often let my head lead the way, which helps remake my heart. My heart, in turn, prompts new analyses. This blog is part of that. Only fourteen months after embarking on the path of poly, I find it hard to remember its origin. How did I find the path’s beginning? How long did I ponder it before I started walking? I surely must credit the influence of queer thinkers, some of whom are my friends—both their analyses and the fact that more frequently than straight people they practice ethical non-monogamy. Although queers less often label it polyamory. That label seems to be more the domain of straight people. I know that I did not buy the poly self-help books until after I’d made the decision to try and de-program myself from monogamy. And I know that it is not something I considered when I made the decision, three years ago, to leave my marriage to a stellar human being. But it was marriage itself that had always felt like an ill fit to me. And I worried about the effect that growing unhappiness would have on our child. But still I was committed to serial monogamy back then. I believed I just had to find the right “one” and everything romance-wise would fall into place. But that did not happen. I tried for a couple of years once I felt my heart open up again after I kept it closed in marriage. But for various reasons opportunities with people I could imagine spending a life with appeared, and then faded. In my age, education, and class range, I meet too many potentially suitable matches who are still tangled up emotionally, psychologically, and financially in monogamous relationships, many of them troubled or unsatisfying. And those who are single are often scarred by their previous committed relationships gone terribly wrong, yet many are still committed to a monogamous ideal. Others see themselves as sexual and emotional mavericks who reject commitment and embrace non-monogamy, but without the openness and extreme level of communication that is a hallmark of the poly ideal. These types are an especially bad fit for me. Like them, I may have early on viewed non-monogamy as a way to have smaller, more manageable connections in the face of “true love’s” absence and in the face of competing commitments, such as work. Work comes first. It not only helps support my material well-being and that of my child, but it is through work that I enact my ethical and political commitments to this world. My work is my spiritual practice. My commitment to egalitarianism further complicates my ability to live up to that idealized form of romantic commitment in our society, monogamous marriage. I am not following anyone around, and I don’t want anyone sacrificing their path to follow me. But unlike the anti-commitment mavericks, I don’t want to reject love and meaningful attachment to other humans in the form of romantic relationships. To be sure, I’m nervous of the pain they can bring: but I know I want it. I am like this in friendship too. I crave platonic ties that enfold love and intimacy that will last to our dying days. Ultimately, being non-monogamous does not free me from the work and emotional risk of love and commitment. Rather, it re-shapes what love and commitment (can) look like, requiring me to negotiate them with multiple partners instead of one. Poly can also sometimes blur the boundaries between platonic and romantic love. A caveat: I’m not knocking sex for the sake of sex. For some people that is what fulfills them. It is not sufficient for the intimacy I crave. Routes after Roots I had an epiphany a decade ago that rootedness in one place—finding that one true geographic home—will never be something I can find on this planet. What a relief to realize there is no one true place for me, and that there is nothing abnormal about that feeling. I could stop feeling like a failure, fickle, a commitment phobe, like travel is just running, like I was doing it all wrong. Along with that realization, came the knowledge that standing still too long has its own ethical risks—complacency, eclipsed vision, and judgment. I must be regularly challenged on the borders of different worlds, always living in translation. Yet after the decade-long sense of disconnection I could never overcome living on a mountainous coast—on land that moves but under skies that are still—I realized that I need to spend more time on flat, expansive land. If not in the spot where I came into this world in human form, it had to be something like it. This land where I live now is warmer than my birthplace, but still the skies are tumultuous, breathtaking and life giving. And I need rivers like I need the roads and the skies. Rivers are the lifeblood of my historic, metaphoric, and literal topography. I grew up near rivers. They symbolize for me leaving and returning in a regular migratory pattern. They are movement and place simultaneously. Like me, like my parents before me, and historically my migratory ancestors, rivers are routed. I live on the banks of one now. Luckily, my work also enables me to travel and to stay periodically in place. I am rewarded for my skills at translation between literal and technical cultures, between conceptual languages. Travel enables me to co-parent my child who lives with my ex-husband during the school year. As soon as I found it, I embraced the knowledge that I am at peace only living en route, leaving for different and challenging far-off lands, then returning to expansive plains and skies, a more tolerant, thoughtful, and grateful person. Routedness, not rootedness, allows me to lead an ethical life.[1] But what of relationships? How could I hope to find someone who can live such a life with me while having their own life? I am fortunate to have encountered a few (potential) romantic partners of whom I was enamored and could take anywhere: curious, tolerant, adventurous, grounded intellectuals who like me come from humble economic backgrounds. Individuals who share my lenses and could grow with me in travel. Yet for a variety of reasons, most of them were ultimately unavailable. But even if one had been available, would I have nonetheless eventually faced the choice of polyamory? Yes, probably. For not only am I routed through different lands, but I am routed in my work. I am fidelitous to multiple institutions and technical tracks. I attribute this second form of routedness also in part to my mother and to the life she created for us as children. She also craves diversity in social relations and from her I learned to build and cherish a stunningly diverse community. It spans many classes, races, nations, technical specialties, levels of ability, sexual and political orientation. I need diverse people with their multiple worldviews and their different knowledges in order to make sense of the world. My family, friends, colleagues, and lovers will often not be comfortable in one another’s presence. But this is the challenge and the existence I crave and which satisfies me: to be continuously routed geographically, conceptually, and intimately. Again, polyamory is for me an intellectual, political, and emotional project all wrapped up in one—each aspect re-shaping the others. But since I am more accomplished at the intellectual than the emotional, I sometimes lean harder on my analytical abilities and my political commitment to non-monogamy to strengthen my resolve to keep navigating the challenging social, moral, and cultural landscape that is poly. If I want a home there, I must help build it. Just like there is no perfect one true love out there waiting for me, just like I have to create and nourish democratic relationships and knowledges, so must I nourish and help constitute the diverse and democratic poly world I want to live in. In the end, polyamory is not only intimacy constituted by love and sex, but fundamentally by openness to multiple connections. It involves emotional, intellectual, and physical plurality rather than “promiscuity,” which is usually negatively defined as entailing a casual, transient, and indiscriminate approach to intimate connection. But the plurality of polyamory can equally be understood not as excess or randomness but as openness to multiple complex connections, some of them not as complete as one might require in monogamy when you can choose only one person. But when they are combined, cultivated, and nurtured, multiple connections constitute sufficiency, and sometimes abundance. The ideal of polyamory requires an honest recognition that life and love are ever in flux. Too often the ideal of monogamy tells us to deny this. It lulls us into thinking we can get things settled, that we are ever safe and secure in our one true relationship. Polyamory does not let us rest in this idea. In its best form, poly leads us to abundance, negotiated and built through work and care. It takes us beyond that sad and debilitating world in which fear of scarcity and deprivation dog us into a severely circumscribed set of choices that we then think we need to live with for a lifetime. Monogamy can be better than that of course, but often it is not. With polyamory as a legitimate choice, I wonder if our standards for and skills with monogamy would improve as well? As Ever, The Critical Polyamorist Note: [1] I owe this language that helped me to understand what I have long felt to James Clifford as he articulated these concepts in his book Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. I am a minority within a minority. I am a polyamorist. Polyamory means being romantically involved with more than one person at a time. With the knowledge and consent of all involved. It does not mean just sex with multiple people. For me and many others it involves the heart.

And I am Native American. No really, I am! My great-grandmother was NOT a Cherokee princess. I am descended from at least four different tribal peoples, and I am a citizen of one of those tribes. And unlike some folks who claim a Native American identity based on some distant and sometimes unsubstantiated ancestor, my entire family—at least the biological relatives—are Native American. Of course, polyamory is not a traditional Native American practice. Or at least it’s no more or no less traditional historically than patronizing your local diamond counter, registering for china at Macy’s, and going down to the little white church. I’ll come back to that in a future blog post. The polyamory expert Elisabeth Sheff notes that people of color and working class people “do not appear in large numbers in mainstream poly communities.” Feminist scholar and critic of monogamy Angela Willey explains that while others engage in varied practices of non-monogamy without necessarily calling it “polyamory” there is a "white hegemony in poly literature" that "has tended to presume a universal subject, neutral and therefore implicitly white, middle-class, college educated, able bodied."[1] As a woman of color raised poor or working class in rural America, although I am now a professional, there are challenges in being an explicit and especially rare practitioner of polyamory. Like many other poly people, I have a university degree. Of course! I would NEVER have been exposed to all of you poly folks if I did not. But after living and traveling in many places, I find that I am still a small town girl in ways that surprise me. My extended family is historically not very formally educated but we were nonetheless a book-reading and PBS-watching lot. I was exposed early on to politically oppositional thinking. My family is anti-racist and anti-homophobic. I am the only one who identifies as a feminist, but most of the women in my family act like they are. I have uncles, aunts, and cousins who are definitely country. Some of them hunt, own guns, and drive trucks. All of the recipes they post to Facebook involve something in a box and or a can. They shop at Walmart. None of us are vegetarians or hippies who practice free love in communes. Well, except me a little. The Critical Polyamorist is an experiment to think through in cyberspace, as an unusually situated person, this adventure that I have embarked upon. This isn’t public journaling. I want to begin a conversation with other polyamorists who feel not only socially challenged in the broader monogamist culture but who also feel culturally challenged within our rather homogenous polyamorist communities. (Disclaimer: I live in middle America, not California or New York. Maybe there are more folks of color who are out as poly in those places. But it’s a pretty pale landscape around here.) I am starting this blog in order to reflect and converse about these struggles with others who feel like me. I know you are out there. I am interested in reaching folks who are grateful for the models other polyamorists provide to love plurally and ethically. Their books and blogs keep me committed to this path on those days when I am suddenly weary or sad. When I feel like falling back into monogamy because it seems easier, because the world is made by and for them. I often hear poly people talk about the lack of models in our society for living this kind of life. We are inundated from birth with monogamy, indoctrinated in its norms and values. Few of us are born into poly families. We often come to this path after living as monogamists for substantial portions of our lives. I have only identified as poly for about a year. At this point I am proceeding with more determination and faith than support or understanding. And for a minority of us within an already poly minority, the examples and support we can find in mainstream poly communities fall short in specific ways as we struggle to do polyamory as particular raced and classed subjects. I identify not at all with the kind of New Age-tinged, communal mode of life taken up by the Kerista Commune in San Francisco in the 1970s that is credited with birthing the polyamory term. And I still see too much for my taste of stereotypical “hippie-dippy” culture in this community. But I am inspired by the systematic shift in both practice and thought that polyamory articulates. I like its intellectual substance. I just sometimes get turned off by its particular form of white cultural drag. I want to find a home in this poly world. If I’m going to do that I need to help make it more diverse. My gift to this community is to provide this place of reflection such as would reaffirm my struggle on those days when I doubt I can do this. So what do I mean by “critical polyamory”? This blog brings critical social theory including analyses of U.S. race and culture to analyze poly life and politics from my perspective as a woman of color, as a rural-born and now urban-dwelling Native American professional. I take the label “critical” not to downplay the radical critique of our society’s compulsory monogamy that polyamorists already engage in. We poly people are critical thinkers and actors who think it is possible to ethically love multiple people simultaneously with the consent of all involved. Polyamory is in this sense inherently and deeply critical. But when I take up the label “critical” it is not redundant. It draws on a broader tradition of “critical social theory.” That is an academic term in which analysis and critique of social problems are not just for the good of knowledge, but they are geared toward social change. Indeed, in pushing for greater inclusion in dominant society, have communities of color not always explicitly called out both obvious and not so obvious politics and cultural practices that exclude our experiences and histories? Critical social theory traditionally brings insights from multiple social science and humanities disciplines (anthropology, psychology, history, sociology, literature etc). I will occasionally add insights from the biophysical sciences to inform my analyses of poly life and politics. That divide between society and nature is a false one anyway. The biophysical sciences also matter very much in understanding our world. And increasingly, disciplines are getting smeared across that line between culture and nature. My kid tells me that I have an “evil sense of humor.” This blog will sometimes get evil, and hopefully funny. All names, locations, and other identifying information will be changed or hidden to protect the innocent, and the not so innocent. Stay tuned for my next post, “Poly, Not Pagan, and Proud.” Yours, The Critical Polyamorist [1] Angela Willey, “’Science Says She’s Gotta Have It’: Reading for Racial Resonances in Woman-Centered Poly Literature,” in Understanding Non-Monogamies, eds. Meg Barker and Darren Langdridge (London: Routledge, 2010), 34-45. |

Photo credit: Short Skirts and Cowgirl Boots by David Hensley

The Critical Polyamorist, AKA Kim TallBear, blogs & tweets about indigenous, racial, and cultural politics related to open non-monogamy. She is a prairie loving, big sky woman. She lives south of the Arctic Circle, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can follow her on Twitter @CriticalPoly & @KimTallBear

Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|